It’s in a women’s magazine at the doctor’s office. With a little ingenuity and the instructions on page 158, your clothespins, ribbons, and orphaned buttons can be repurposed, it says, into a Nativity scene. The word “repurpose” is a new one, with a scent of wistfulness about it, as though it pines for the days when everything still had value. What’s now called repurposing didn’t used to have a name. It was just what you did. Your wedding dress reemerged as baby gowns, your skirts were pieced into quilts. Nails were straightened and string saved for certain future use. Like as not, these days, things are repurposed into decorative items that nobody really needs. You probably even have to buy the clothespins, now that we bake our laundry dry.

So every day we try to stay just ahead of our own debris field, but ultimately, everything is repurposed. Supposedly that’s the way the whole universe operates, some of its dust congealing into stars, and some into the planets the stars keep as pets, and every so often some of the dust motivates itself into life like us: self-conscious, tiny sparks that crumble fast away.

The stars we see may be long gone. There’s some evidence that the present is all there is, but we’re not comfortable with that, and we enlist Time to keep the present from getting all jammed up. Still, there’s no making sense of the thing. If time does flow, it doesn’t do it evenly.

Dave and I have a little mountain cabin in the moss-happy woods that we go to when we can, and it’s somewhere around 1960 in there. The forest fends off the Internet and cell phones sulk in silence like artifacts or curiosities. We do have electric lights, unless a gust knocks a tree across the line and sends us back another century. Not long ago, we brought in my childhood chest of drawers, a familiar piece that traveled unchanged from Virginia to Montana to Oregon over the course of fifty years, but after mere weeks in the damp of the cabin it clamped itself shut and refused to open. So we decided to make another trip to bring up open shelving to stack our linens in.

When we got there, the place was damper than usual. A large window lay shattered to pieces inside and out. We did a quick inventory and discovered a number of items missing that had been repurposed into methamphetamine. It was nothing we hadn’t seen before. Thirty years ago, we might have felt seriously ticked off. We might have nurtured our wounds as though ignoring them was doing them a dishonor, but that was thirty years closer to our childhoods, and time has contracted. Now we just sweep up glass and skip ahead to the time when we aren’t thinking about it anymore. The back of the warped chest of drawers is repurposed into a temporary window and the rest repurposed into kindling. We’re buttoned up and to the weather, and it’s starting to look like some of that is on the way.

“Beer?” Dave asks, waggling a bottle from the refrigerator.

“It’s kind of early for beer, isn’t it?”

Dave was already pouring. “We’re on mountain time.”

And mountain time runs different. By evening it has nearly come to a stop. A wafer of the ocean a hundred miles west of us has repurposed itself as snow, and it piles up outside our wooden window and buries all clamor, without and within. Two companions who had not always been old sit in front of a chest-of-drawers fire with glasses of beer. They’ve still got a little more spark before they crumble.

Happy new year, friends.

It sounds as if you have managed to find a way to escape the clutches of Time in that cabin. That is a precious thing. In the cabin, it is always just "now". The concept of time is merely a human invention, and like most things is an excellent servant but a terrible master. Enjoy the Timelessness!

I wonder if I can blame my punctuality problem on being always in the Present.

Happy new year to you as well!

Thanks!

"Two companions who had not always been old sit in front of a chest-of-drawers fire with glasses of beer."

Made me choke up, remembering my companion who had not always been old, and evenings in the cabin in the woods, him reading, me examining my mushroom haul of the day.

Sweet memories!

Aw. The best.

Ah, your soft side is showing big time, Murr. All the best in 2016 to you and Dave. And family.

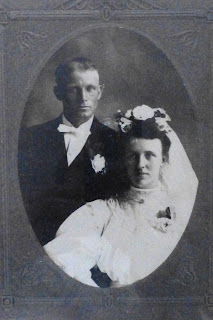

Speaking of family, who's the lovely couple in the wedding photo, may I ask?

My mother's parents, Hans and Petra Skari. As you can see, I still have the bodice to her wedding dress, stained and rumpled, but the skirts were repurposed.

So cool to have something she actually wore, no?

Mom gave me that when I was still in high school. I can't remember if I tried it on then. Seems like something I would have done. In any case, it would be interesting to put it on now and see how it drapes. My mother and grandma had the same body as I do.

It is very thrifty of you to use their bodies.

Well, two-thirds of us did live through the Depression.

In another life I knew all of the world's Time Zones and could measure their time in relation to Greenwich. Today, Time is an errant creature which lives, mostly, just down the street. But inside my head things happen in totally unrelated time zones.I find I can move quite comfortably from steamy tropic to cool mossy Oregon.

And money not spent on air fares is repurposed for wine. I think the modern folk call it January so, cheers! to January.

I like it inside your head. In fact, I'm inviting myself.

Just holler and I'll throw down the rope ladder.

I'd figured you for a knotted-sheets girl.

Time? An illusion. And a delusion. Says the woman whose early training makes her chronically punctual.

A very happy New Year (and life) to you.

Actually, I'm not that bad now. I used to be terrible. I'd leave at the exact last second that would get me somewhere on time if EVERYTHING went right. I guess in some ways I feel as though I have more time now, even though I don't.

That time which speeds up with every tick of our human measuring device. The idea that we are now inching toward two decades into the 21st century is making my head spin. Happy 2016 to you. And I think you should spend your time wisely by being at this cabin as much as possible.

I think you're right. I'm penciling in next week. Don't worry, I'll leave y'all sumpin' to read.

beautiful

Repurposing sounds more comforting than recycling, it sounds more like the newly repurposed items will actually be used and re-loved, while recycling sounds like everything melted down and remade into gee-gaws no one wants.

Happy New Year.

Let's all see what we can make out of the bits of the old year.

This is a very sweet post, whether you intended it that way or not. I'm about to become a grand mother for the 2nd time and I'm re-purposing my childbirth experiences for my daughter. They are mostly as useless as a clothespin Nativity and yet, they have a place in the greater scheme of things. Thank you and happy New Years to you and Dave and Pootie and the birds and all that you care about.

They do have a place in the greater scheme of things. That's one cool thing about time. You get enough of it, the greater scheme comes into view. Unimportant things drop out. Grandchildren are front and center. Love, in general, is front and center.

I have done you a disservice. In my head, your writing is funny, quippy, full of beats. I'm not sure I'd completelty realized how beautiful it is, too. This is so lovely.

I like to toss in one of these every now and then just to throw you off.

Beautiful post to start the year with!

Oh, now I suppose you're expecting MORE?

Okay!

Man, I wish I had a cabin to run to when life is getting too heavy!! You lucky Murr you!! I would be laying in a hammock, staring at the trees, listening to the birds, and feeding the squirrels.

ACK! We do not feed the squirrels! If we do, we suffer the Wrath Of Dave!

I love your "…every day we try to stay just ahead of our own debris field…' turn of phrase! Murr, you are a gem strewing treasures to your loyal readers! Looking about, my debris field is closing in on me. Note to self: we need vacuum cleaner bags.

I was thinking Dump Truck, but I think we're on the same page.

So this is what you do in your blog: you take a factoid and repurpose it into something different and so much better — in this case a reminder of all that really matters. This one had both Alan and me in tears. Happy New Year, Murr. I love you.

I love you too.

Stephen Hawking meets Henry David Thoreau. Nice post!

Thoreau saves string. Hawking has a theory about that.

"Now we just sweep up glass and skip ahead to the time when we aren't thinking about it anymore."

Good job,honey. This reads like one of those posts that just writes itself. That "skip ahead" thing? I do that all the time now. It could be confused with wisdom by someone young. It can't be contrived, though. It's a gift of age, a special species of forgetfulness, of sorting. I call it lethefulness. (btw, belaymylast is my Dave. See above.)

I did not know that. I get to meet the whole family!

Did you get a lot of snow in the recent dump on the Cascades? In the picture the cabin looks like one of the USFS cabins built and leased out in 99 year leases. My kin had a couple of those up at Elk Lake.

Why don't you and Dave take a trip east and talk some sense into those loonies in the Malheur?

It is one of those forest service cabins, yes. But the 99 year lease is a thing of yesteryear. They were replaced by twenty-year and then five-year leases and now they're charging enough that some families have to bail out on their cabins. Oh! Malheur. Stay tuned: Wednesday Murrmurrs, Malheur SOLVED!

Thank you, your article is very good

viagra asli usa