So, cool! New Orleans recommends “restrained maintenance” of its historic buildings to preserve their aging patina, and I’m all in favor. I wondered just how aged they could be. What’s the oldest building in New Orleans? Who knows? My own house is older than the city of Portland thinks it is. Memories are short, and their curators dead.

So, cool! New Orleans recommends “restrained maintenance” of its historic buildings to preserve their aging patina, and I’m all in favor. I wondered just how aged they could be. What’s the oldest building in New Orleans? Who knows? My own house is older than the city of Portland thinks it is. Memories are short, and their curators dead.

But 632 Dumaine Street is a valid contender. It now belongs to the Louisiana State Museum, and they’re proud of it and furnished it with appropriate antiquities. It’s an early wooden entry dating possibly to 1726, before they started making nice brick buildings with what we shall call unpaid labor. “Possibly,” because whenever it was built, it had to be rebuilt after a fire that took out 80% of the city, but a bunch of its components were presumably recycled.

It’s not that impressive to me, even as an “excellent example of Louisiana-Creole residential design.” It looks like a box with garages underneath. No doodads. No wrought-iron frippery. I’ve seen similar apartment complexes dating from the 1970s here. But heck. Antiquity, and all that. It’s got verandas front and back. Well, so do I, and no one’s giving me period furniture.

1726 would certainly be plenty early for the town, which was officially founded in 1718. Where I live, you’re not going to find anything of that vintage. The oldest standing building in Portland dates to 1857 and it wasn’t until the 1860s that anyone found a mud-patch dry enough to plunk a house down. My sister Margaret’s house in Maine is quite a bit older than that and there’s nothing distinguished about it at all. There are lots of old houses in Maine and they’re still standing, because anytime it looked like they were going to keel over, someone slabbed on another section to hold it up. Now they lurch across the landscape in the Early Catawampus style and are casually maintained with redundant paint.

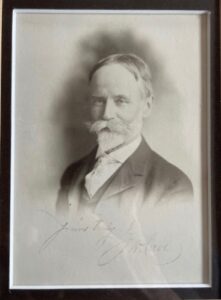

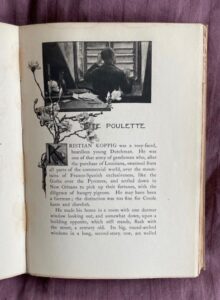

The Dumaine Street house in New Orleans caught my eye, though, because it is nicknamed “Madame John’s Legacy,” after a character in a short story by George Washington Cable, a then-renowned New Orleans author said to be the “first modern Southern writer”—the John The Baptist to William Faulkner’s Jesus. George Washington Cable is famous in my house for being my great-grandfather. So I pulled out my copy of “Old Creole Days” and read the short story in question, “‘Tite Poulette.” Two pages in, Madame John is bequeathed a house on Dumaine Street, sells it, puts the proceeds in the bank, and the bank promptly goes under. That’s the whole mention, in a much longer story, but it was good enough for the citizens of New Orleans to decide this house was Madame John’s Legacy, and it might as well be, because Madame John is fictional.

The Dumaine Street house in New Orleans caught my eye, though, because it is nicknamed “Madame John’s Legacy,” after a character in a short story by George Washington Cable, a then-renowned New Orleans author said to be the “first modern Southern writer”—the John The Baptist to William Faulkner’s Jesus. George Washington Cable is famous in my house for being my great-grandfather. So I pulled out my copy of “Old Creole Days” and read the short story in question, “‘Tite Poulette.” Two pages in, Madame John is bequeathed a house on Dumaine Street, sells it, puts the proceeds in the bank, and the bank promptly goes under. That’s the whole mention, in a much longer story, but it was good enough for the citizens of New Orleans to decide this house was Madame John’s Legacy, and it might as well be, because Madame John is fictional.

Cable had a wry and humorous cast to his prose and mainly wrote about class, caste, and color in Creole New Orleans, and this story is typical in its sly indictment of miscegenation laws. Meanwhile, white New Orleans was embarking on its post-Civil War enterprise of terrorism and re-enslavement. The Jim Crow project was clipping along pretty well, featuring decidedly unrestrained maintenance of a permanent black underclass, with help from the KKK and various paramilitary groups. Cable was not on board with the program, and—by the genteel standards of the time—he was mouthy. By 1885, he had been made to feel considerably less welcome in his home city, and he moved north, where he continued to take eloquent potshots at the Southern racist establishment from a pleasant perch in Northampton, Massachusetts.

Remarkable, really, all of it. Only three generations back, someone in my family predated the entire city of Portland by fifteen years, and white supremacists are still going strong.

“Restrained maintenance”… I like that. I’m going to use that if someone gives my overgrown yard and driveway that is fast losing asphalt and turning into a rutted, rocky drive the side-eye. In reality, I’m tired. And I see no point in spending a lot of money on repaving the driveway at my age. For what? The neighbors?

Our house is Early Catawampus, as you said, also. It’s around a hundred years old, and a police captain had it built by “calling in favors.” As you can imagine, when people do things “as a favor” and not for actual money, they cut corners. Nothing is level, the windows are slightly different sizes even on the same wall, they used inferior mortar on the stones surrounding the basement level, so the basement leaks. Thank goodness they at least managed to put in a French drain! But we love our home. (Paul calls it “our crooked little home.”) And fortunately it is a ranch house, so it’s easier to navigate as one ages.

Wow, a hundred-year-old ranch house? Our cabin is so crooked that if you walk from one corner to its opposite in a room, you get bigger. Or smaller.

Cool! An Optical Illusion Home! Basically a 3D funhouse mirror! One thing about my home that is upsetting (at least to me): The people who built it were tall. Some kitchen cupboard shelves are high, but I could — previously — reach them with a stepstool. I knew that I was shrinking when I could no longer reach the top shelf with a stepstool (I was only 5 feet tall to begin with, FFS!) Now I have to ask Paul (who has also shrunk from 5’11” to 5’9″) to reach the top shelf for me or get my grabby stick. But he still towers over me. If this shrinkage keeps up, Peter Dinklage will tower over me.

Hear ya. You know I call Dave my “Extenda-Dave.”

Great story; you come from ‘good’ stock!

I think most of it is good–there are some darker portions! The Brewster lineage seems dour.

From that impeccable source Wikipedia…….”This house is briefly seen in the 1994 movie Interview with the Vampire in a scene where caskets are being carried out of the house while Louis (Brad Pitt) is describing Lestat (Tom Cruise) and Claudia (Kirsten Dunst) going out on the town. Part of 12 Years a Slave was also filmed at the house.”

Well how about that. Somebody owes Madame John some fictional money.

I’d like to know what the heck is a French drain?

I like the look of those old houses but would hate to live in one and have all that maintenance to keep up with.

It’s just literally a drain in a low-lying part of the concrete floor. I don’t know if it drains into the sewer or just the ground.

I think of French drains as being run outside the house from the downspouts and buried in the yard with holes in it to get the water away from the house. Also they have Gruyère in them.

Brewster Academy? George Cable pianos? Where does it start, where does it end?

You mean George Cables’ piano?

I googled and am thinking I could use a French drain or two around here but I doubt very much that “Housing” would allow me to have them installed. I rent a flat in a Public Housing block.

It’s just as well. French drains are so much more supercilious than the regular ones.

Is it true that the French call them English drains and the English call them German drains?

I lived in NOLA for 10 years and never knew the legacy of the legacy of Mme. John’s. And certainly not your connection to it. Thanks for that. I’ll never look at the 600 block of Domaine in quite the same way…