|

| Photo by Nina Harfman |

My recent musings in which I implied that salamanders are the crown of Creation were not meant to state anything that wasn’t already obvious. I mean, look at them. But it got me to thinking about a scientific maxim I learned in college: ontology recapitulates phylogeny. It’s a dense phrase. It is, of course, designed to make people feel stupid, then defensive, then irritated at smartypants elites, then prone to making snide references to Obama and his “faculty lounge” as though educated people should be scorned, and before you know it they’ve voted in a bunch of scoundrels wholly devoted to getting themselves and their friends rich enough to buy out God. So probably the phrase should be retired.

|

| Photo by Nina Harfman |

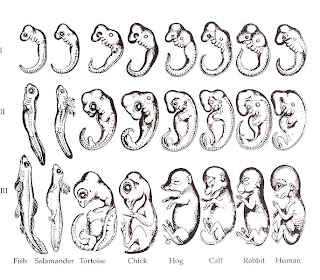

But what it means is pretty cool. The idea is that in the course of developing from egg to embryo to fully-realized critter, we exhibit the stages of our own evolution. We start out sort of wormy, then begin to sprout the accoutrements of our species, reabsorbing our tails and fattening our heads and whatnot. Mom’s a little uncomfortable in the second trimester when we go through the triceratops phase, but things smooth out. It’s a very attractive notion. It was first proposed by Ernst Haeckel who drew a picture of the various embryonic stages, pointing out the early salamander. That’s the hook, right there–who wouldn’t want to claim a salamander in her heritage? I’ve noticed that most people who have looked into their own genealogy have been able to trace back to Charlemagne at some point. We like to think well of ourselves. This just ups the ante.

Trouble is, apparently it’s not true. I am old enough to have learned it in school, but it’s not true. I also remember looking at a world map in fifth grade and all of us kids pointed out what is perfectly obvious: it looks like the Americas had somehow split off from Europe and Africa. We got on our tiptoes and reached up to trace the map, our voices rising in excitement. The teacher smiled at us indulgently and shook her head and began talking about our delightful imaginations and segued right into something about Santa Claus that we also didn’t want to know.

So she was wrong on two points, if you include Santa. But that’s science for you. We don’t always get things right, but eventually the weight of evidence is brought to bear, and minds are changed. Sometimes it takes a while, because scientists are human too, and they see what they want to see.

|

| Photo by Nina Harfman |

That’s one of the differences between science and religion, at least the ones that purport to know something. It’s hard to knock a good religious story off stride. Once we’ve got a good narrative going, we don’t really want to examine it too closely. An Iroquois succumbing to deadly curiosity could march all the way around to the bottom of the world and back around to the top and approach the shaman and say, “you know? I checked, and the world really isn’t balanced on the back of a turtle after all,” and that will be the last sound you hear before the thunk of his severed head hitting the ground. For a lot of recorded history, curiosity killed a lot more than cats.

But I’m a curious soul, and I have to go where that leads me, rather than where I want it to. I’m really sorry I didn’t get to spend a fetal week as a salamander, but that’s life.

All the splendid portraits in this post were made by Nina Harfman over at Nature Remains. She’s a great photographer with some sweet subject matter and she’s pretty dang limber, too.

"before you know it they've voted in a bunch of scoundrels wholly devoted to getting themselves and their friends rich enough to buy out God."

I loved that line! Indeed, a Republican Montana Legislator last year introduced a bill declaring that global warming wasn't happening, at least as a result of human activity, but that it was good for us anyway. Who needs science when we can just pass laws ordering the universe to be as we want it?

http://data.opi.mt.gov/bills/2011/billhtml/HB0549.htm

When folks think we can choose between science and air conditioning, we're in big trouble. By the way thanks for your patience, guys. I've been stuck in beautiful downtown Charleston WV for a few days now and the internet and I are just now getting reacquainted. I sure hope they let me fly out tomorrow.

It was that line that prompts me to write and say, "I swear to god, that woman must own a time machine!"

Living the nightmare.

But ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny is such a great phrase! How can it not be true? Oh, it's that whole, there are more than four elements thing again, isn't it? Well, earth, air, fire and water was good enough for my ancestors…

I thought the four elements were carbon, zinc, potato chips and beer.

Are you saying the earth is not balanced on the back of a turtle? An advanced scientific theory at the time when all the while theologians thought the world flat. Turns out they, the theologians, were right. There's even a book about it… The World Is Flat, ergo, must be true.

It's turtles all the way down.

I cannot tell you how happy it makes me to find out it's turtles all the way down. I know it can't be salamanders. They're too squishy.

Antiintellectualism is rampant… and ulimately profitable (in the short run) I love you pig post. We live next to a mega hog farm. And giant lagoons are the coming rage in a regionof karst. Bad idea.

Wait. Did you just call me a pig post?

I thoroughly enjoyed this little foray into scientific theory, Murr. Your sense of humor continues to delight. You are definitely a curious soul, and who says you didn't spend some time as a salamander in another life? 🙂

Actually, I think that's what I get to be next time around if I play my cards right and my soul is pure.

It all makes sense to me; the only time I wished I didn't know so much about embryology was when I was pregnant. (The doctor gave me a simpler book, without any pictures of abnormal development.)

It is logical and possibly certain (among some geologists) that South American and Africa were once connected. You kids were not wrong. You just had one of those rotten teachers who have no curiosity.

It's a known fact, now, that South America and Africa were formerly connected. But not too long ago, it was believed that continents could not move. The incident Murr described probably hapened before continental drift was discovered — the point being that science corrects itself and adds new knowledge as new evidence is found, whereas religion clings to old ideas regardless of evidence.

Yup, they were postulating it in the sixties, but it was not accepted knowledge until late sixties or so. Mrs. Parks was a little mean about the whole thing, if you ask me.

When I took Geology I in 1963 they were still teaching the non-tectonic theory (such as it was). Now we have the obvious jigsaw proof, the continental drift theory, and both of those backed up by geological strata and fossils, and there are still folks who wonder. Probably the fossil part.

Me, I'm not going to believe they drifted that far in 6,016 years, no matter what "proof" they come up with. Can you imagine the quick stop?

I adore salamanders! But the axolotl is the ultimate in adaptability, IMHO. They live and reproduce under water until and unless the water supply dries up. Then they lose their gills, their skin toughens up, and they become salamanders. Talk about survival skills! Just had to throw them out there as they have a special place in my heart. Loved your post. I'd gladly admit to be related to salamanders…or axolotls. 😉

I've never seen an axolotl but I did a report on them in fifth grade. Mrs. Parks didn't find any fault with that, as I recall. I'm still waiting to use that word in Scrabble.

I recall that when I was in France there were lots of salamanders carved into the walls of the chateaux we visited. King Francis the First loved salamanders and used them as his symbol. I never leaned why.

That I'm going to have to look up. King Francis the First. My man. Thanks.

By the way, those are some mighty handsome salamander photos you've got there. If you ever come out east, be sure to look for our glorious red efts, perhaps the cutest little amphibian on the planet. They frequent forest trails and are hard to miss with their scarlet bodies and big, orange spots. Most of them are rather docile, too.

I just spent the week at the New River Birding and Nature Festival here in West Virginia and scored three red efts and a slimy. It was a good salamander week. One of Nina's photos got selected for the Ohio Wildlife stamp this year. Or something like that.

Speaking of religion, and intending no offense: we were in eastern Kentucky a couple of weeks ago, wandering around in coal mining museum where the exhibits talk about coal being the result of pressure for several million years, as I recall. And then I find out that prevailing religious thought in the Bible Belt is that the earth is 5,000 years old. I wonder how the miners reconcile that.

Probably just added more pressure?

I think we look more like manatees at Stage II than salamanders. And what about Cornish hens for Stage III? And then, *presto*, we split from Europe and become North America! Or the people of Walmart. The fish is the only one who looks like (s)he knows what (s)he's doing from the get go.

I'm a little punchy. Have been gardening all day in the pollen.

Somebody get this girl some Benadryl STAT!

Wow. I thought I was the only kid who had figured out continental drift and plate tectonics from looking at the big world map in front of the class room! And my teacher's reaction was just as you described–"Impossible, Linda, since the continents are fixed." Once I discovered the truth, I wished Miss Alexander were still alive so I could go back and say, "See?!"

I'll bet you anything this same scenario was played everywhere at that time. A lot of times the really big ideas are not well accepted at first.

Why, we've been on the back of a turtle for even more than 5,000 years. It must be a pancake tortoise, and the bottom of the earth is just as flat as the top. That makes me feel so safe.

Hey, now I do too. I'd been visualizing a really large box turtle and that is unacceptably tippy.

Albeit less-witty than the above comments," here's the thing about science…it's true whether you you believe it or not!"

I don't know–I'm still kind of hoping those people are right about the rapture, because I'd like them to go away.

My goodness! I haven't heard "ontology recapitulates phylogeny" since I was a little girl! My father used to trot it out on odd occasions. His definition of it was "like begets like" and was used to its highest purpose to explain why my brother was going to be a boy, and not a kitten. Elaine M.

I think he was wrong about what it meant, but I'm going to assume that your brother did not turn out to be a kitten. Although that would have been super cool.

Not true? But that is my favoritest phrase of biology! I'll say it anyway and claim poetic license. Or – what is it they use in the Bible? Metaphor! When John says, "Behold the lamb of God," he is not telling us that Jesus had a sheep with him. So I'll stick with the ontogeny wheeze religiously.

I thought Jesus WAS the sheep. Or lamb. And that he was a particularly gifted lamb,that taketh away the sins of the world. Which he can't do fast enough, in my opinion.

Amen, sister! But I think he keeps taking, and the world just keeps on giving. That, "Go and sin no more" thing is really tough.

wow, what a mouthful!

Two thoughts came to mind while reading this post and the usual equally entertaining comments: 1. Scientists should listen to kids' theories of how the world works-the scientists might learn a lot; and 2. Was the turtle shell upside down or right side up? Either we all would be balancing on top of a bell curve, or the universe is contained within a bowl-intriguing image either way.

I also feel as though I had a little science today.

Based on our success as a species, I'd say that at least part of that bell curve theory is right on.

I always thought that the smiling baby signs that say "at 12 weeks I had fingerprints!" are funny. Why don't they say, "I also had gills and a tail!" Guess gills and tails on humans aren't considered cute.

A friend has a t shirt that says,"Stop plate tectonics!"

Yeah I learned "ontology recapitulates phylogeny" in college biology… well I didn't really learn it because I always had to look it up. Damn if I didn't just recently as well find out it was wrong! I liked that teacher and he had beautiful teeth; but just goes to show you that you can't trust people with perfect teeth. Actors and politicians. Look at John Edward's teeth… goddam perfect, nothing else about him though.

What were we talking about?