They’ve got this genetic test they can do now so you can find out if your child is likely to excel in athletics. This test is particularly useful if your own observational skills are meager. They look for some kind of gene marker for speed and springiness. You can swab the inside of your child’s cheek and send in the DNA to the testing lab and for $160 they’ll let you know if he’s got potential for zip and is just being lazy, or if you should plan to spend the next eighteen years rolling him over on the sofa to prevent sores.

I suppose this kind of information helps parents with their day-to-day child micromanagement. With one tissue-culture they can find out if they should be pushing the soccer drills and saving up for a genuine Rumanian coach, or just buy the kid a clarinet and hope for something better next time.

My parents would have had it easy collecting my DNA, because I move slow and drool. But it would have been a giant waste of time. Testing me for athletic prowess would be like thumping a bowling ball for ripeness. I’ve never had any skills. If I were ever to excel in an Olympics, it would have to be a special one just for me, featuring trudge-scotch, stationary jumprope, tether-feather, and Red Light Red Light. One thing that was probably a plus for my mother was that she only needed to check on my whereabouts every half hour or so, because I couldn’t have gotten far.

It was awful in grade school. Every day at recess the two kids who usually got to be captains chose their teams, and it always got down to me and the kid with flippers. I didn’t feel bad for myself. I had no part of my self-worth tied up in sports ability, but I felt sorry for the captains. I wouldn’t have picked me either. They’d stand there, shifting their weight from foot to foot, all anguished, and finally one would say “oh, I guess I’ll take him,” and the flippered kid would hitch on over, and the remaining captain would close his eyes in resignation.

I was exciting to watch in softball games, although it put the coach on edge. If I was on second base, there was always the possibility the batter would lap me before I made it home, and technically you’re not supposed to score the fourth run before the third. I read an article about the genetic differences between good athletes and us more torpid specimens, and took some comfort in it. It turns out that muscles are made up of slow-twitch and fast-twitch fibers. “So the sprinters naturally have a greater proportion of quick-twitch muscle strands,” I read to Dave. He looked at me and said, eschewing the minced word, “you don’t have any of those.”

He has plenty. He runs bases like he’s an electron, and it’s a good thing, too, because the boy has a mouth on him. I, on the other hand, have had to develop my powers of ingratiation. Pokiness helps hone a sense of humor. You might be just as mean and opinionated as the next guy, but if you can manage to be adorable about it, people let you get away with stuff.

So I can’t see my parents shelling out for a genetic test for athletic ability. I can see them watching me execute a crumpled cartwheel or throwing a ball at my own feet and thinking: maybe she can draw.

Oh yes. We were brought up to believe that everyone has a special talent. And I have to say that its getting a bit effing late for mine to emerge now. I was, like you, one of the last picked for any sporting teams. I cannot draw. Or paint. Or sing. With my luck my special talent will become evident on my death bed.

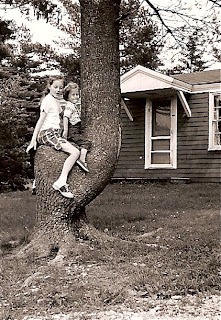

You can hang from a tree branch rather well. You have the evidence to prove it! Alas, and alack, I was not known for my athletic prowess, either. My basketball dribbling might have won me a spot on the special Olympics team. I laughed out loud so many times. Once again, you've made my morning a good place to be. Thank you. Great pics!

Cheeze, you are so darn funny. This is probably one of the the few blogs where I really do LOL, not just once but through out. Your muscles may be slow twitch but your brain is super fast twitch. Thanks for the great start to a cold morning.

This was hysterical. I love the rolling over on the couch to prevent bed sores thing. The pictures were a great addition. This is my first time here, and won't be my last.

My son seems to be made up mostly of superball fibers. He can't help but bounce.

I have slow-twitch muscles. I was technically an excellent swimmer – perfect form. But I was slower than cold mud in the pool. And I'll never run fast, which is why I do marathons.

Ahhh, a MurrMurr with my morning tea! You may not have any fast-twitch muscle fibers, but something weird has happened to your brain and those fast-twitch humor fibers are firing wildly!

I also have only one blog I follow that makes me smile before I even pull it onto the screen. 🙂

I've learned more from this post than I learned from the whole newspaper today!

It's nice to know someone wasn't traumatized by being chosen last. I never thought to sympathize with the team captains.

I seem to have been uniquely gifted with a peculiar athletic magnetism: the kind that got me hit in the head with the basketball, in the shoulder with the softball, in the shin with the hockey ball. On the other hand, I KNOW when a bowling ball is ripe. Mine's been pretty smelly for a while now. I think I need to keep it in a bag separate from the shoes…

I don't know about this twitch stuff, but I know why I'm not fast—I'm 5'10" tall and it takes longer for a tall person to get the "move" command from the brain to the feet.

Really.

Gee, what's my excuse? Signed, Stumpy

Because of my stature (which I like to call "fine") I was never tall enough for basketball, large enough for football, or attention-deficit enough for baseball. But in junior high school, the bullies managed to encourage my development in running.

So though by High School I was still the last pick for most PE class sports, but I was at the top of the pick list when it came to do Track.

Unfortunately sadistic PE coaches created a monumental disdain in me for all sports. The sad consequence of this is that I therefor find nothing else left to watch Sunday on any TV channel other than "Deadliest Catch" on the Discovery Channel.

I was always the last one to get picked for teams too, unless the girl who weighed 180 pounds showed up. My parents didn't need to test me, though. Neither one of them could do sports worth beans; they were just amazed that my sisters could actually run.

At least you could climb trees! And hang from them too!

Reading all the above comments, I see you don't really need my screams, gasps and raves about your amazing ability to make me laugh. However, as Mae West said, "Too much of a good thing is wonderful" so I will add my voice to the pack.

Murr, you ARE the greatest. I love you.

Thanks!

Gol! Thank YOU, Lo!

When I was a kid I played all kinds of sports, now taking the stairs is sport enough. Some things are overrated, and sweaty

What the HAIL did you do to that tree y'all are sitting on? It looks like a llama!

– Col

Oh, I am so gratified to hear about your lack of athletic prowess. I have a l-o-n-g history of complete failure. In elementary school, the teachers made me wear a helmet. In high school, I was placed in "Remedial PE" for people who had just had open heart surgery. I hadn't.

As a guy who spent his h.s. years in an intensely jock culture, cursed with an older brother who was varsity this & that and a Nat'l Merit Scholar to boot, and who struggled to be allowed the privilege of warming the bench during my senior year, this post was a blessing, as are all your blogs. Thank you, thank you …

Oh cripes, I can see every parent in my suburban neighborhood wanting to get their kids tested. They'll want to know if a scholarship is imminent before they buy their next beemer. Ack, they'd buy it anyway.

Btw… Were you on my softball team? 😉

Well there you go, Murr. I wanted to be a concert pianist but I couldn't read music…and I didn't have a piano. So there's always something in the deficiency department, isn't there. Anyway, I for one am really thankful that all your fast twitch muscles ended up between your ears. It's even better that most of them are bunched up and firing at the speed of light in the funny part of the brain. The feet might be shuffling but the neurons are tap dancing like Fred and Ginger.

I wasn't athletic growing up, I always seemed to ran a grade slower. Then I figured out I was sent to school a year earlier for some reason and no one wanted to listen to me complain. In high school I started to catch up to those captains who didn't pick me and…

Just kidding!

Thanks for the laughs from another girl "whose name was never called when choosing sides at basketball."

Thanks for my Thursday giggle, Murr…I grew up playing with my younger brother and the two neighbour boys, so I was athletic at home…I was always mystified about why I was picked last for sports teams at school. Maybe it was the thick glasses and the lift on my shoe? Sigh…

Wendy

You've pretty much summed up my athletic abilities there too. My Olympic sport would have been Klutziness. I can trip over my own feet and fall up the stairs like nobody's business.

But you can write and make people laugh. I'd rather be stuck with you in an elevator over an athlete any day.

♥Spot

To the Elephant's Child: I think that the powers that be allowed for two groups on our big blue marble…Talented folks…. and their audiences. Where would these talented folks be without us? We nuture and appreciate them, providing gentle corrections and insights….heck, sometimes we even throw money their way….kinda like a cross between a muse, a rich Uncle and really nice English teacher. See? We ARE talented!!!

Donna

Note to self: do not read Murrmurrs while traveling via Amtrak sitting in the Quiet Car – signs indicate that passengers must refrain from loud talking or cellphone use, and it turns out doing a spit-take followed by an eruption of deep laughter is also frowned upon. It's been a dark time missing your last few posts, my friend, glad I'm back!

Ha, great post! No wonder my parents made me take those piano lessons, I have slow-twitch fibers coming out of my ears.

"Testing me for athletic prowess would be like thumping a bowling ball for ripeness." What a great line.

It was a healthy way to grow up not meshing your self worth with your lack of athletic prowess.

I run, well, ok, did the snail crawl, over from Arkansas Patti's, and am I glad I did. Thanks for putting a kick in my vocals this morning. I couldn't stop laughing as I related to everything you experienced. Laughter really IS the best medicine, as me Pappy said just before he passed away after reading a good mother-in-law joke. Nuff said.

BlessYourHeart from your newest follower

The only zippy genes I have in me are in my fingers. Man, can they zip across a keyboard. Unfortunately, they can't produce anywhere near the guffaw-producing prose your "slow and steady wins the race" genes can.

This was a delight!

I think I must have started out with those zippy twitch fibers, but sometime into my teen years, I was transformed into torpor slow-twitch girl. I can hike, but don't make me run. I'll complain for days.

Arkansas Patti sent me your way with promises of a good laugh. I am not disappointed – very funny. BTW-speaking twitches…what does that twitch in my eye mean?

That twitch in your eye means you need to take a nap. That, beer, and bigger pants are my answer to everything.

A gang of us used to play Looser's Softball every Memorial Day. We neede two ringers – guys who could actually get the ball over the plate. the rest of the teams were made up of people who couldn't run, pitch, hit, catch, or throw. You got as many swings as it took to hit the ball. Or if you got tired of swinging, you could take the base. If you could actually get under a ball and catch it, even if it bounced out of your glove, it counted. But the runner still got to stay on base. The only way you could actually be put out is if you knocked over someone's beer. And if you tried keeping score, you were sent back to the house to get more beer, and no one would tell you what happened while you were gone. Then the Emericks started bringing the toxic waste margaritas and other people wanted to actually USE the diamond and the game sorta fizzled.

I inherited my absolute lack of athletic ability and a couple of downright lazy genes, and being the good sport that I am- I passed it on to my children. Twitch on!

Hey Murr, you might be surprised to learn that they aready had this test when I was born! The ol' man was really hoping for a Whitey Ford or (looking at the large red meathooks on me in the crib) at least a Jack Dempsey. So he said, "Let's do the swab, Honey!" And he and Reba Mae did it and sent it off to the capital (Columbus)for testing.

Well, I was 61 on my last birthday…and I'm still waiting for the results to come back from the lab. Last time I made an inquiry about it, they told me the results had been sent to the Ohio State Museum of Natural History and were on display next to the two-headed sheep fetus that they keep in a jar.

Your little face in the top pic – that IS you, right? – gives a whole new meaning to the term BAD-minton.

Great piece as always, Murr.