So I’m on Twitter, I guess. Now what?

This will no doubt resolve itself in time, but for now the thought of plunging in and learning the ropes makes me spin into reverie. This is a cherished ability of mine, to look clear-eyed into reality and veer away, and it’s a significant component of my mental health regimen. In my reverie there’s an on-ramp, and a man is walking up it towards me. That’s me at the top of the ramp in a long homespun dress and a bonnet, a goose quill behind my ear. Sure, it seems a little girly now, but that’s what everyone is wearing, and you don’t have to put on any underwear. The man gets closer and closer. He has a broad, infectious smile. Why, it’s Dwight Eisenhower, sure as shit! He gets up to where I’m standing at the top of the ramp and sweeps his hand downhill, indicating a mighty tempest of traffic going every which way. He’s so friendly and pleased I can’t help but smile back. But I’m uneasy. I’m sensing disapproval from my father. My father did not like Dwight Eisenhower.

“Why not?” asks Mr. Eisenhower, which startles me. Then I realize Mr. Eisenhower and my father are both dead, and had probably already had words. Daddy didn’t mince them. He flang them out fully-syllabled in impeccable order, such that, even listening, you could tell they were spelled correctly, and anyone arguing with him was likely to realize he was losing even if he didn’t know why. Mr. Eisenhower was still smiling. He was hard to dislike, actually.

I had to think about it. Most people liked Ike, and the main reason Dad didn’t was that he wasn’t Adlai Stevenson, near as I could make out. I was too little to understand exactly why we weren’t Republicans, but we sure weren’t. Being a Republican meant you had to join a private golf club and drive an Oldsmobile to it, and Daddy was a Peugeot-to-the-hiking-trail kind of fellow.

“Well,” I said, thinking back, “I’m not exactly sure. I was pretty young. There was that whole Richard Nixon thing, and his obsession with the Communists.”

“Was your father a Communist?”

[Pretty much. Let’s just say he might have had Bolshevik sensibilities.] “I’m not sure it’s any of your business,” I said, getting my back up a little. Dad might have been on to something. “My father didn’t think much of Republicans, and that was well before they all turned into lunatics.”

“True,” Ike said, his smile faltering a little. “Well, you’re a nice girl. Interesting get-up. Weren’t you born in 1953?”

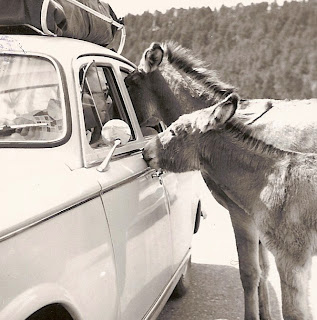

|

| Daddy, the Peugeot, and friends |

I was, but I can wear whatever I want in my own reverie. I would have backed all the way into the nineteenth century, if I weren’t conflicted about the whale oil.

“Don’t mind me. You can wear whatever you want in your own reverie. Now,” Mr. Eisenhower went on, putting a hand on my shoulder and fanning the other towards the swirl of traffic below. “Have a look. It’s my Interstate Highway System,” he said. “Do you like it?”

It looked pretty scary, tell the truth. I edged a bit further into the past. “I don’t rightly know, Mr. Eisenhower,” I said. “I reckon I can purt’ near walk just about anywhere I’ve a mind to. And if there is somewhere I need to get to in a hurry, why, I can just ride my old donkey. I have a whacking stick to get ‘er going with, too.” I did, but I couldn’t bring myself to use it. Don’t tell Mr. Eisenhower, but I’d just carry it under my arm and bounce up and down on my ass, going unhh, unhh, unhh. If the donkey felt like going somewhere, off we’d go. It was good enough.

“You’d never use a donkey-whacking stick,” he said, reading my mind again. “You’re not the type. Try my Interstate Highway System instead. You’ll love it. In no time at all you won’t know what you did without it.”

I transferred the goose quill to my other ear. “I don’t know,” I said. “I guess I don’t see the point. Everything I need is right nearby.” More important, I am uneasy about taking on something I’m currently quite capable of living without, and then not being able to live without it. Seems burdensome. Pick up too many things you can’t live without, it seems like you’re setting yourself up for a flame-out. Autopsy results indicate she died from a lack of an ATM, wasabi peas, and early internet withdrawal, compounded by the end of Boston Legal reruns. I gave Mr. Eisenhower an apologetic look. “It’s so busy and loud. I don’t know how to drive.”

“Nothing to it.” Mr. Eisenhower opened the door to a big, shiny car. It might have been an Olds. I sensed a cosmic raised eyebrow from my father, but I couldn’t help but look inside. At least it was a standard transmission; that wasn’t Republican. I got in and sat down, smoothing my dress over the bench seat. There were no seat belts, and plenty of room for the donkey. “I don’t know,” I repeated.

“Nothing to it.” Mr. Eisenhower opened the door to a big, shiny car. It might have been an Olds. I sensed a cosmic raised eyebrow from my father, but I couldn’t help but look inside. At least it was a standard transmission; that wasn’t Republican. I got in and sat down, smoothing my dress over the bench seat. There were no seat belts, and plenty of room for the donkey. “I don’t know,” I repeated.

“You’ll love it. Off you go,” Mr. Eisenhower said, grinning wide, leaning into the window and smacking the shifter into neutral. The Oldsmobile edged down the on-ramp and picked up speed. “The manual is in the glove box,” he hollered. I pawed at the glove box in a rising panic but found nothing but neatly folded state highway maps and a bar of dinosaur-shaped soap from Sinclair Gas. Below me the traffic was a blur. I braced for a terrible collision but when I opened my eyes again I was coasting to a stop on the highway with the traffic parting smoothly all around me. I sat in the car and looked around, then perused a map before snapping back to the present.

So I’m on Twitter, I guess. If you see me, honk. I’ll be the one in the bonnet.

Those are mighty modern looking sunglasses you're wearing in the reverie, Murr. I loved, loved, LOVED this look back into it though. Your commenters are usually very clever themselves, but I'm first and I can just do anything I want here! Thanks for the morning giggles.

Your comments about picking up things you can't live without: I'm reading this while visiting friends on a farm in the middle of, well, lots of farms. My host said, "If you had the choice of TV reception or Internet reception, which would you take?" We both agreed Internet, and in fact their old TV sits unused in the basement… Fortunately, wasabi peas aren't something we desire out here in nowhere, so I think we are safe from flame-out for a while.

Maybe that's why I haven't gotten to tweeting…I don't have the right outfit. Thanks for the chuckle and the insight!

Roxie sez

You stage the most wonderful photos! (well, the melting cat was staged for you but you know what I mean) I took a spin on the twitter and ran out of gas wayyy too fast.

If Twitter is for Twits, what is the interstate highway for?

When I was a child, about a hundred years ago, my family was, as far as I can figure out, the only family whose parents were Democrats in Bellingham, WA. When my father started making serious money, he gave a lot to Democrats running for office. One of his proudest moments was when he was at a reception in D.C. during Nixon's reign of terror; Nixon was walking through the reception,shaking hands with everyone, but when he got to my father, he stopped, looked him straight in the eye and said, "I remember you…" and walked by without shaking hands.

A) Tell me you're not standing on the Failing Bridge.

B) Tell me why on this big green earth a town would name a bridge the Failing Bridge.

Oh, reveRie, not reveLry. I thought that was an odd party dress.

Love it. And I too worry about adopting more things that I then can't live without. So I am (as yet) twitter and facebook free.

You are completely mad.

Twitter is, in my view, even sillier and more cumbersome than Facebook.

How do I know? I tried it. Hated it. Abandoned it.

I've heard that Nixon used that snub on quite a few people.I remember when he was a coat-tailing lawyer for Joe McCarthy; a good enough reason even then to to mistrust him/them.

I've just been reading that massive 'bodice ripper' (a new experience for me, bodice rippers, not reading) 'Outlander' by Diana Gabaldon. I just knew that you, like the heroine Claire were actually a time traveller, literacy, humour, irony, spelling….all antique stuff please don't bugger it up by tweeting, your wordiness is so appealing.

I'm a FB person, and I post short, Twitter-like comments. I get distracted too easily to pick up something else.

That's funny, when my husband talks, you can tell the words are not spelled correctly. Like, at all.

So, does that make you a twit?

My parents were republicans but they were Chevy folks. Must have been the income level…. a

Should have named this one little bridge on the prairie.

All I remember about my dad were his pull my finger jokes. He died early. Probably because he voted for Nixon when he ran against Kennedy.

Loved this post, and your unique sense of humor. Good luck with Twitter. I "got on" a while back, but don't so much with it. Just as before, I'm still a much better tooter than tweeter.

Next Monday, there will be an award for you on my blog, should you wish to accept, dear lady.

Carole, you must be SO proud! Nixon wouldn't have recognized my father, even though he might have been on a List. Kat, I'm one bridge north of the Failing Bridge. Hey, I can read. Origa-me, I'm addicted to Gabaldon. She's one smart cookie. Thanks for giving me permission to be an antique.

Susan, gee, thanks! One more reason to get up in the morning.

I never know what to say when I stop by here. You're just so damn brilliant and witty and creative that I become totally tongue-tied from awe – and yes, more than a little envious. The juxtaposition of the interstate highway system with the information highway, the contrasts between your dad and Eisenhower (who was accused of being a Commie sympathizer by the Birchers as I'm sure you know), and bringing the donkey into play – all delivered with one succulent line after another – are all signs of a major writing talent. Yes dammit, I'm jealous as hell.

As far as twittering – got on it and took the first exit I could find. It's like trying to get on a subway car during rush hour when everyone else is trying to get off. Really fabulous piece.

Don't be shy, Leslie. Ear-flapping praise is always welcome here. And no, I didn't know Ike was on the List, too! Pretty cute for a Republican.

Hey, I'm on "Hit and Twit", too. Well, does it count if I simply have an account and don't tweet? I'm curious…what would you wear if you were reverie-ing with Nixon? Great post.

You could try jumping into Twitter as I did, without a clue about hash marks or @'s, figuring if Ashton Kucher could handle it, a genius like me would get it right without even checking out the Help link. Come to find out, there's a protocol and a particular sort of Gen Y funny bone required to keep from making a damn fool of myself. But what's the point of passing sixty if you can't make a damn fool of yourself with impunity, right? Pull on out, girl.

Adlai was brilliant, articulate, and wonkish. Ike was a populist and he had that catchy slogan, "I Like Ike." It was America. We're terrifyingly predictable.

Kutcher, not Kucher. I rest my case.

Love this-and humbled by it. Damn! I could never come up with something like this, let alone pull it off. Plus, I don't have one of those homespun dresses……

My grandfather, a staunch Republican (mom claims he would have voted for the devil if he were Republican-I claim the devil is Republican) must be horrified that all of his grand- and greatgrand- children are staunch Democrats. Such is life. Tweet away!