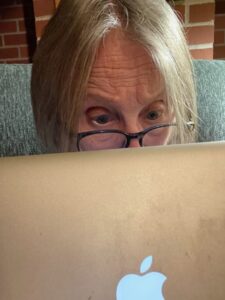

The only thing that was clear was that I was overdue for a round with the eye doctor. Even random strangers can tell. I’m playing flagrantly wrong notes on the piano, with conviction, because even with my special piano glasses I’m seeing six lines on the staff instead of five. I’m spreading my fingers on paperbacks to embiggen the print. I’m holding my laptop up to my face and peering over the top of my glasses, while the lower half of my face goes slack and toad-like. In theory I have three areas of focus in my glasses but I keep looking for a fourth in the balcony.

The only thing that was clear was that I was overdue for a round with the eye doctor. Even random strangers can tell. I’m playing flagrantly wrong notes on the piano, with conviction, because even with my special piano glasses I’m seeing six lines on the staff instead of five. I’m spreading my fingers on paperbacks to embiggen the print. I’m holding my laptop up to my face and peering over the top of my glasses, while the lower half of my face goes slack and toad-like. In theory I have three areas of focus in my glasses but I keep looking for a fourth in the balcony.

I’m strenuously near-sighted. When I take my glasses off, everyone disappears altogether, and my fitness for polite society disappears along with them. I gaze stupidly into the fog. I scratch my butt. I dig for boogers.

You know you’ve got good friends when they watch you mining away one knuckle deep and say “Aw. She probably needs a new prescription.”

So I went to the eye doctor. I love the eye doctor! Nothing hurts and there’s no untoward poking. Plus, when she asks you to pick A or B, and you pick B, she says “Good!” every time, even when you think you got it wrong.

I’d been told I had cataracts but they were waiting for them to blow up into something really turgid and annoying before doing anything about it. Maybe my cataracts finally matured, I thought. Then they can just set them on fire or impale them with a moonbeam or whatever they do and I’ll be able to see like an eight-year-old again, preferably a different eight-year-old than myself. I couldn’t see the blackboard when I was eight. Cataracts are cloudy areas in the lens, and really not noticeable seven months out of the year in this climate, but a girl can hope.

I’d been told I had cataracts but they were waiting for them to blow up into something really turgid and annoying before doing anything about it. Maybe my cataracts finally matured, I thought. Then they can just set them on fire or impale them with a moonbeam or whatever they do and I’ll be able to see like an eight-year-old again, preferably a different eight-year-old than myself. I couldn’t see the blackboard when I was eight. Cataracts are cloudy areas in the lens, and really not noticeable seven months out of the year in this climate, but a girl can hope.

First the doctor hauls out the machinery and tests for glaucoma by blowing wind up your eyeballs’ skirts. She does them one at a time. After the first one, I watched—from my side—in a state of resigned amusement as she twiddled her apparatus in the wrong direction, looking for my other eye. It’s there. It’s just implausibly close to the first eye. If they were any closer they could correct everything with one monocle. If they were any closer the bridge of my nose could be replaced by a small stepping-stone. Eventually she located it. All was well.

Then on to the other machine. There is a spot to lean your forehead on and a nice chin rest. After a moment’s reflection, I chose to rest my primary chin and let the others bob around below and talk amongst themselves. There was a bright fog in the viewfinder which, after some twiddling on her part, resolved into a very sharp, very bright balloon a mile down a straight road. It was a thing to behold. I could not imagine having the ability to make out that much detail in a distant object. Why, if I could see that well, I wouldn’t have to make anything up. My fiction writing might suffer, but my night driving wouldn’t be so loud.

This is amazing, I thought. By “thought,” I don’t mean the rational kind. That also disappears when my glasses are off. What I thought, in my state of wonderment, was it would be so cool if they could somehow take this big equipment and strap it to my face so I could see like this all the time!

Second thought, several moments later: Oh. Like glasses.

Well, she said my cataracts weren’t ripe enough to pick yet, but she had two new prescriptions for me, Regular and Piano. Next stop, Optician. My self-esteem had dropped a notch when the doctor couldn’t locate my left eye, which totally exists, but I was recovering. And now I had a chance to get nicer glasses than the ones I picked out before. This would be great!

to be continued.

The good news is when your cataracts do ‘mature’, the outpatient operation to put a new lens in will solve your glasses problem, somewhat.

I was nearsighted, 20/200 for decades. Got cataracts, had the operation, and now eyesight is 20/30. I only need reading glasses.

There is a type of replacement lens that ‘adjust’ so no glasses are needed. When I got my lens replaced it was quite new, and I opted for the proven ones.

We’ll see. Apparently there had been no change. I’m more like 20/700, but I’m not actually excited about not wearing glasses. I look a lot better with them.

How timely. My eye exam is on Tuesday. I hope they find my left eye, too. Let us hear your new 5 staff piano playing when this is all finished.

Some day! I will report: I now have my new glasses and the PIANO GLASSES TOTALLY WORK! Both previous versions were kind of or a lot off.

My grandmother got to the point where she was parking by Braille. Thank goodness modern medical science has progressed to the point where you will not need to do that. Please do let us see the new glasses. (My friend’s wife had to have her left eye removed. When she went to the optometrist with her new glass eye, they did the test where you cover your eye and tell them what you see. Then they asked her to cover her other eye and tell them what she saw. One wonders if the technician was paying attention.)

I park by scraping my tire violently against the curb.

OMG- me too. Only the best of us now this tried and true method

I’m due at the ophthalmologist too. One of the few benefits of the pandemic for surviving Boomers is that we didn’t get excessive medical care, which is actually a thing in our insane system. We had to do a risk/benefit analysis before running in for any medical care. I feel healthier as a result, whether I deserve to or not. I felt so good, in fact, that I indulged in an entire wardrobe of rx eyeglasses ordered online and made in China. I’m embarrassed to say how many colors of frames I have, but I can’t need a new perscription…so, that many.

Nance, a book I mentioned here I think in the last post: Less Medicine, More Health by Dr. H. Gilbert Welch says that there is too much testing and unnecessary procedures. Part of it is due to litigation. But mostly because it is so lucrative. I guess the doctors tell themselves “oh, insurance will pay for it.” But what about those of us who have REALLY crappy insurance? Doctors perform procedures that aren’t needed all the time. My elderly uncle was talked into having a circumcision. He died of a puncture from a colonoscopy a short time later. (They had found cancer, but he had to spend the next few months at the V.A. before he died, instead of getting his affairs in order — which he had to delegate to me.) I have a hearty mistrust of Western Medicine as it is practiced now.

I blacked out at “talked into having a circumcision.”

I’d have to have that kind of online experience where they actually send you a bunch. Glasses don’t fit me.

“I’m spreading my fingers on paperbacks to embiggen the print.” I actually saw my 2 year old grand niece do that, and then look at me in bewilderment when nothing happened.

I wasn’t lying about that.

“I’m spreading my fingers on paperbacks to embiggen the print.” I actually saw my 2 year old grand niece do that, and then look at me in bewilderment when nothing happened.

How timely! I just came from the eye doctor yesterday myself.

They had no problem finding my left eye but it is failing rapidly. That eye, which used to be the “good eye,” is now blurry no matter what lens they try. Apparently its cataract is really ready now to be extracted. I almost did it last fall but never got around to it, so here I was again at the eye doctor having the same conversation, but this time I am really going to schedule it. As soon as the summer is over, lol.

I’m super nearsighted myself and am used to having the superpower of being able to remove my glasses and see the tiniest print imaginable as if I’m looking through a magnifying glass. So the idea of needing reading glasses after getting a corrective lens inserted doesn’t appeal to me. After watching a little video on an iPad they gave me while I was waiting for the doctor, I may opt to go with “monovision,” where one lens is corrected for distance and the other for reading. I had contact lenses like that back when my eyes weren’t so dried out that I couldn’t wear them anymore, and I got used to it easily. We shall see.

I was truly laughing out loud at your descriptions of your adventures.

Ooo! My contacts are like that! One for distance, one for midway. But I still need reading glasses.

I had those contact lenses also! But once I decided to get glasses so I could rest my dried-up eyeballs in the evening, I never put the lenses in again. I likes the glasses.

Murr, the only doctors I see regularly are my dentist and my eye doctor, because those are quality of life issues. I’m not looking for longevity. But in the time I do have, I want to be able to chew solid food (am a Foodie!) and see well enough to read and drive (reading and garage-saling are favorite pasttimes!)

I know that my vision is worse than it used to be. I also am really near-sighted. And getting more far-sighted also as I get older. Phyllis (my eye doc) gives me contacts that give me better far-vision in one eye, and better mid-vision in the other. I still need to use reading glasses when I wear contacts, though, for close stuff.

She started asking me at each visit, once I got older “Are you experiencing any flashing lights?” She never asked Paul, who is far-sighted. One night, I experienced this in my left eye. I was freaked and called her really early in the morning. She brought me in that morning to dilate my eyes and have a look-see. I asked her then, why she always asked ME that question and not Paul. Apparently, when a near-sighted person gets older, their eyeball shrinks a bit and tears away from the retina — which — rarely — can lead to a retinal tear. I was okay, and when it happened a year later to my right eye, I didn’t panic, but made an appointment at a decent hour. But I DO have more floaters now, which can be a fucking pain in the ass! If I tilt my head, they swim back to another position. Still. Hate the floaters!

Most of my floaters drift just ahead of wherever I’m aiming my eyes. So I can try to chase them but I never catch up.

My son had a floater that didn’t float but impacted his vision to the degree he lost his pilots license. He had a vitrectomy and is good now. Scary stuff.

Wait! Don’t you need your Vitre? Or is that something you have two of?

Yo, Murr. Best word of this post = embiggen. Thank you. I will use it from here on out!

I had a big tumor behind my most nearsighted eye (left). Opththal’ist decided to do a cataract surgery and wait a year to have the tumor removed. What huh?! By the time I had to have it done in Phoenix (I live in Medford OR and we snowbird there), it had grown. Brain surgery was 7 hrs. Now when I look straight I can’t see to the left (as when I’m the passenger to the driver of the car). I no longer can drive. Ticked off about that!! So besides my neurologist in Phx, I also have an optholmologic neurologist who keeps my eye in check. “Check – still can’t see!”

I’d love to have glasses that fix it. I wear reading glasses for small stuff. Most of my regular reading is done on my electronic tablet so I can embiggen (thx Murr) the letters. Since I don’t drive, I read a lot while hus Denny drives. We had to come up from AZ to Oregon last weekend for medical last weekend when the weather/rain broke for a minute. I read and slept a lot. I highly recommend the device “Flippy” from Amazon to balance your books/tablets on.

As for playing piano…I looked a lot like Murr’s photo when I tried playing a couple of days ago. Me oh my oh. Or maybe I just don’t remember how! Must get it tuned. Same piano we bought on the 6th floor of Meier & Frank in 1962. The tag is still stapled on the back. I could be a concert pianist with a little help. ☺ Or not. Y’all take care. We return to AZ when the weather is OK. It’s supposed to snow in Medford and the mtns tonight! Yee haw.

Good grief, Mari. That’s horrible. And I didn’t invent “embiggen.” Lisa Simpson did, I think.

When you’re ready for new lenses, the surgery is a breeze.

Good to know!

Waiting for ripe cataracts is no longer the rule in Pittsburgh. You cannot read road signs on the highway and can’t even get to the corner if there’s any mist or fog. You step right up. Yes, it’s like a boat buyer’s dream for the docs. I had surgeries 3 yrs ago and have been so glad. Get the customized lenses. Use Care Credit for 1 year without interest.

Gotta admit, the two new prescriptions seem to be right on the money, so I guess my cataracts are still in hiding. In training?

Timely for me too! I just saw the optometrist yesterday. She measured more things than I thought could be measured, then told me I have the very earliest stages of cataracts (“Everybody gets them eventually”) but it’s too early to do anything about it. Everyone says cataract surgery is routine these days, but my family’s experiences with medical issues have taught me to ignore the admonition still given to med students that goes “When you hear hoofbeats outside your window, think ‘horse,’ not ‘zebra’.” These days I think “zebra.” Marsha had cataract surgery and lost almost an entire year of reading and writing, which almost ended the book she was writing once and for all, but she did eventually get that old engine in her head up and running again. Anyway, the optometrist said I have something (whose name I forget) that means that the normal flora on my eyelids is starting to grow out of control, so I’ll have to wipe down the edge of my closed lid with something containing either tea tree oil or hypochlorous acid, and if I start immediately I’ll avoid beaucoup trouble later on. That didn’t worry me — I’m used to tea tree oil in my dandruff shampoo and hypochlorous acid in the disinfectant I spray the shower with twice weekly — until I found that the Kaiser pharmacy had no such formulation for their eyelid wipes. On the way home I stopped at the biggest CVS I know of and found the right stuff. My distance vision turned out to be good enough for the DMV, but I could do better with glasses, so I will — bifocals so that if I have to read a map (yeah, the paper kind), when I pull of the road and unfold it I won’t have to switch glasses. She thought it was interesting that I have a chromatic aberration — I can’t read blue “neon” lights at night, and a blue Christmas light at a distance looks like a magenta dot with a violet halo. She was sorry she couldn’t do anything about that, but I allowed that it does not affect my life a bit. I should stop rambling now.

Now all I can think about is “zebra.”

Wow, I have an issue with blue light disappearing when I look directly at it.

When I wore contacts, every light at night had a gigantic halo around it. Not sure I’ve noticed anything about blue light. But I drive like Helen Keller.

You have to be careful with tea tree oil, as it’s very drying. I put a dab on acne when I get it (YES. At MY age.) and it dries the pimple overnight. If i dare to put it on the same area the next night, my skin peels a bit. I wish I had known about tea tree oil when I was young and had lots more acne. The antibiotics and stuff that my dermatologist prescribed did no good at all. I still had acne, but redness and irritation as well. AND those ever-popular yeast infections.

Maybe the drying effect is what makes it work in my shampoo (I’ve always been an oily-haired guy). I guess I’ll see about the eyelid wipes eventually. I thought I was getting acne late in life but it turned out to be a severe case of rosacea, which if untreated was going to leave me looking like a pimpled smallpox survivor. Lucky for me, antibiotics (topical plus pills) are keeping it at bay. After some time with those I experimented — stop the pills and see what happens, stop the topical and see what happens — and I found I still need both of them. Somebody online suggested coconut oil, but that was ineffective. So that’s two more prescriptions I can’t quit on my ridiculously long list. And speaking of yeast, I get bleeding yeast infections in the fold under my too-large belly (yes, great image, I know, sorry) if I don’t use Clortrimazole there daily. And life goes on…

Boy, we’re all a sorry bunch that hang out together here, with our various maladies that come from aging. And, okay, you win the yeast infection story. Mine just made sex irritating, but some guys do that just on their own. 😉

Good one!

Ummm- not everyone loves getting the new lenses after cataract surgery- me … for instance. How I have so much difference between the distance and the corrected vision up close I have to have super strong reading glasses- and then I also have computer glasses and I can’t see s***t if its tiny print or dim light. Well, I have normal pressure glaucoma, too……… I once had a doofus os a tech tell me I had great pressures “Congratulations” in the eye puffer machine-. my response- “hey, doofus, I have normal pressure glaucoma and a 40% vision loss……” Just saying when we get to a certain age they need to LOOK at the optic nerve……

Uh-oh. What happens if the eye doctor can’t see either?

After reading all the comments here I’m worried now about my own cataracts and how well I’ll be able to see after the surgery. I am long sighted with crossed vision and every time I get new glasses they are never quite right. I’m glad I don’t drive.

As a group here, it sounds like we’re a right mess!

I am in the same boat piano music wise. The same way I can’t see to thread a needle (hand or machine) and we won’t even go into the fact that I use readers to be on the computer.

I can thread needles and such if I take my glasses off. I just have to worry about doing things in the correct order, so I don’t put my glasses on the fabric and stab myself in the eye.

More anxiety to add to my already full basket.

If you develop holes in your basket it all works out.

I had cataract surgery on both eyes over 10 yrs. ago and all has been good. When I play piano I sit on 2 of my rather thin kitchen chair cushions. This lifts me up just enough so that I have no trouble reading the music. Try this before buying special piano glasses. It was just that I wasn’t sitting high enough on the bench!

Nope. My bench height is a very precise thing–low. My little legs fall asleep otherwise. Anyway–my new glasses work!!

I had cataracts removed and all went well, but the replacement lenses can’t take care of the astigmatism. So I have glasses for distance, computer, and reading. I play handbells, and I’ve found than none of the glasses work as well as just my bare eyes because of the relationship of my eyes to sheet music when I’m standing up.

I’ve known women who had up to three pairs of glasses on lanyards around their necks.

Paul sometimes wears two pairs of glasses over his eyes: His prescription (if he isn’t wearing contacts), plus blue-blockers if he’s on the computer. He’s not four-eyes, he’s six eyes. I tell him that he needs another pair over all that so that he can be eight-eyes and legally be declared a spider. (I love spiders, so that’s not as weird as it sounds. Oh… wait… maybe it is.)

Geeze. I have an appointment with a new-to-me eye dr. on Tuesday, and after reading all the comments, now I’m afraid to go! All I want is an updated Rx.

Just tell them you don’t want your eyeballs drilled out and you should be fine.

To Jeremy; I found that using sunscreen daily was the best method to settle down my own rosacea, a dermatologist suggested it when I was in my thirties. No medication was ever suggested. For the fold under my own too large belly, I just swipe my antiperspirant deodorant stick under there right after I do my underarms each morning. Keeping that area dry is key to reducing any painful redness and possible infection.

Sunscreen sounds interesting, though I don’t know why it should work. If it’s the sun-blocking, I don’t think it would help as I already get very little sun exposure. Or is it one of the other ingredients? As for the antiperspirant, I have bad reactions to those after just a few days’ use, so I save them for special occasions. At home it doesn’t matter, as my wife has a seriously deficient sense of smell, which at times can be very convenient. For me, that is.

I use Gold Bond medicated powder under my boobs and at the elastic line at my private parts since I get itchy redness there from time to time – is this the Golden Years they talk about?

Teeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeee

Emmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmm

iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii

everyone!

It’s not my fault. I was talking about eyeballs.

Actually, the TMI makes me feel a little better about my own maladies. Sometimes it’s because someone else is experiencing what I am. Other times, it’s a sigh of relief: “I may have THIS problem, but at least I don’t have THAT one!”