“Sorry I’m late,” my friend hollered out, trotting up to me on the street corner.

“NO,” I said, leaving my mouth hanging open. My mouth was waiting for the rest of the phrase to emerge. My friend looked startled. She wasn’t that late.

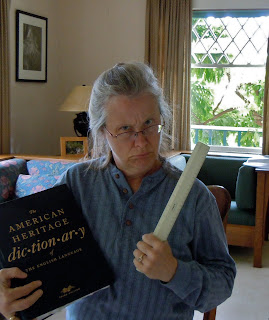

The problem was I was caught midway between trends and had stopped my phrase before saying “no problem” but hadn’t quite accessed the new wording, “no worries.” If you were able to peer into my brain at that moment, you would have seen it all pixelated and momentarily frozen, waiting to resolve. My VCR brain was still piddling around looking for a tape at the video store when the world had gone completely DVD. Or whatever it is they’re using now. It’s hard to keep up.

When I was in my teens, one way you could tell if someone was an old fart was if they used the word “groovy.” No one I knew ever once said “groovy”–that was an urban myth. I do distinctly remember hearing the word “hang-up” for the first time, and my whole generation was flinging that little locution around with confidence inside of a week. So I consulted a young person a while back about “word up.” What did it mean? He explained. “Okay,” I said, feeling it out, “so if you said ‘it sure is hot today,’ I could say ‘word up?'”

“Or just ‘word,'” he offered. I tried it out.

“But really, no one says either of those anymore,” he finished. Well crap. I was trying to hop a train that had already left the station.

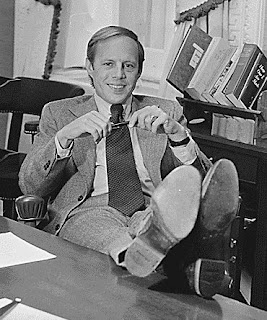

We all learn our language in a big mass, all at once. When you meet someone new, and she has a cute way of saying something, your brain takes note of it and shoots it out of your own mouth soon after, without your even telling it to. Stuff gets into the community system. Back when Watergate was the only Gate around, the lawyer John Dean was on TV frequently, explaining what had happened “at this point in time.” It sounded ever so exact. Before Mr. Dean, things happened “at this point” or “at this time” but no one ever had that stop-action precision that he was able to bring to the picture. Mr. Dean said it, and infected other people, who began to say it on TV, and now we can’t get rid of it. It’s not a deliberate choice. You’ll just say “at this point” and the “in time” hitches right onto it. Unless you’re curmudgeonly, like me, and make a point of not saying it.

We all learn our language in a big mass, all at once. When you meet someone new, and she has a cute way of saying something, your brain takes note of it and shoots it out of your own mouth soon after, without your even telling it to. Stuff gets into the community system. Back when Watergate was the only Gate around, the lawyer John Dean was on TV frequently, explaining what had happened “at this point in time.” It sounded ever so exact. Before Mr. Dean, things happened “at this point” or “at this time” but no one ever had that stop-action precision that he was able to bring to the picture. Mr. Dean said it, and infected other people, who began to say it on TV, and now we can’t get rid of it. It’s not a deliberate choice. You’ll just say “at this point” and the “in time” hitches right onto it. Unless you’re curmudgeonly, like me, and make a point of not saying it.

Some of these phrases can be traced back to a particular day, or point in time, if you will. During the Clinton impeachment embarrathon, someone wrapped up his testimony by saying “at the end of the day,” meaning “ultimately” or “when all is said and done.” It sounded very poetic, and I took note. The very next day, an entirely different senator concluded his statement by saying “at the end of the day,” and I thought: uh oh. Sure enough, the phrase went viral (“went viral:” c. 1994). Every time I hear it now it’s like catching the edge of a buried splinter. My reaction is so profound that I recoiled when I read about the sun dipping below the horizon at the end of the day, and had to remind myself that that is, in fact, what it does at the end of the day. Oh. Well then. Okay.

It’s not just phrases. Even voice patterns sweep across the population in an epidemic fashion. Like most old farts, I got irritable about the questioning intonation that young people, almost without exception, began to employ a few decades ago. I just found it so annoying? I never thought I’d miss it until it got replaced by the current mode wherein all speech peters out into a little gravel bar at the back of the throat, as though the speaker has suddenly become way too tired to prop up her own larynx. Everybody of a certain age speaks that way now, even professional radio announcers.

Some stuff just gets mentally embedded and lurches out willy-nilly. A friend told me proudly that her young son had gone out Christmas-shopping “on his own recognizance.” I don’t think she meant anything by that, but she’d already said “on his own” and the “recognizance” didn’t come unhooked. It just trailed along like verbal toilet paper on the conversational shoe. In the same manner, people are always sweating “like a banshee” or driving “like a banshee” when all banshees ever did was wail.

People used to wait

for other people and have conversations

about things. Now they wait

on people and have conversations

around things. And then there was the first time I saw a poster that said “What part of NO don’t you understand?” I thought it was very clever. So did everybody else. Now we keep running into stuff like “What part of you can have my gun when you pry it out of my cold dead hands don’t you understand?” Not so clever. Kinda dumb, really.

Since I’ve set myself up as the expert in trend-spotting, I’ll let you in on the latest one. You will now hear it twenty times a day on NPR interviews. Here it is: “That’s a really great question.”

It replaces “Um.”

We all learn our language in a big mass, all at once. When you meet someone new, and she has a cute way of saying something, your brain takes note of it and shoots it out of your own mouth soon after, without your even telling it to. Stuff gets into the community system. Back when Watergate was the only Gate around, the lawyer John Dean was on TV frequently, explaining what had happened “at this point in time.” It sounded ever so exact. Before Mr. Dean, things happened “at this point” or “at this time” but no one ever had that stop-action precision that he was able to bring to the picture. Mr. Dean said it, and infected other people, who began to say it on TV, and now we can’t get rid of it. It’s not a deliberate choice. You’ll just say “at this point” and the “in time” hitches right onto it. Unless you’re curmudgeonly, like me, and make a point of not saying it.

We all learn our language in a big mass, all at once. When you meet someone new, and she has a cute way of saying something, your brain takes note of it and shoots it out of your own mouth soon after, without your even telling it to. Stuff gets into the community system. Back when Watergate was the only Gate around, the lawyer John Dean was on TV frequently, explaining what had happened “at this point in time.” It sounded ever so exact. Before Mr. Dean, things happened “at this point” or “at this time” but no one ever had that stop-action precision that he was able to bring to the picture. Mr. Dean said it, and infected other people, who began to say it on TV, and now we can’t get rid of it. It’s not a deliberate choice. You’ll just say “at this point” and the “in time” hitches right onto it. Unless you’re curmudgeonly, like me, and make a point of not saying it.

Word up? Awesome. Catch you later.

I have a dear friend who recently, when I'd tell him some tale of woe, would say, "Sorry about it." I wondered where on earth his 60 year old brain got that, until I heard him talking to his 28 year old daughter and he told her something to which she said, "Sorry about it."

For a while, everything was "cool" and when you'd say something unbelievable, you'd hear, "Dude!" I'll never forget the first time I heard a respected nurse practitioner friend of mine use it as I was telling her something crazy a patient did. Made me want to rub my eyes and make sure it was her standing in front of me.

Fun post Murr!

Good on ya! My personal not so poetic peeves: to make a long story short (which the person saying it never does); you go girl (go where?); that old 90's rube – dialoguing (ick); and My Bad…(wherin grown ups revert to toddlers when they's screwed up). Outta here!

Thanks for the background on some of these expressions. Just one question, is an "entirely different senator" more or less reliable than a slightly-different senator?

The only time I ever heard 'that's a great question' it was from someone who followed it up with 'but I'm not going to answer it now.'

I can remember back in high school (Pleistocene era), trying to make it though a day without using any slang. It was much tougher than I expected. Way!

I used the word, groovy, not long ago. I beat myself afterward.

Someone once said that when you hear, "That's a good question," you're about to get a lousy answer.

Do all servers etc in your area proclaim whatever choice you make as excellent? It's big here — or was several days ago.

"…trailed along like verbal toilet paper on the conversational shoe." Absolutely perfect!

Way extreme post. Yo.

Awesome! is the fingernail-to-chalkboard for me.

My wife is one of those people who says "sweats like a banshee" or "hurts like a banshee." It drives me nuts, but I've decided to stay with her for the time being even if she wails like a banshee when I correct her.

You go girl. Don't forget "literally." As in, "she literally jumped out of her shoes." or "he literally exploded with rage."

Read "The Tipping Point" for some insights into how trends get started…very interesting!

Dang, Frank! "Slightly different Senator" would have been so much funnier. Servers here think our choices are "awesome" or "sweet." Or excellent. Any way you put it, I am apparently the maestro of the menu.

I was going to say what Caroline said. How do you come up with these witticisms? Keep it real, man. Hang loose.

And another pet peeve: "in regards to." Ugh!!

Like, this was really, like, fun to read? Ya know, like, nice, and stuff.

Like, that was like, really fun to read, and stuff, like, ya' know?

Ack! My comment was there, then it wasn't, and now it is again! Sorry. Like, and stuff.

🙂 I have been like way startled to hear my wife begin saying "dude!" It just comes out of her mouth. This is a mouth that mostly stopped picking up new lingo in the interval between "cool" and "rad," you understand. Same age as yours or mine. But, "dude!" she exclaims, and I answer "dudette!" And a look of horror settles on our poor teenager's face.

I know, right??

What exactly does that mean? Does it mean the same thing as uh-huh?

I love this post. Do you tire of hearing me say that? Because I do, over and over. And at the end of the day, at this exact point in time, you've nailed it dead to rights.

xoxoxox

jz

"Sick" seems to be growing in favor, while "Insane" is waning. Both mean something is really good. I must confess to having been a bit confused when I heard "sick" used the first time, because it was a referring to a somewhat ambiguous situation involving musical taste. Being on the far side of curmudgeonry, I thought the commenter meant the music was awful — as I did.

This post made me laugh.

Julie said it before I could…working at a college, I hear "I know, right?" at least once a day. It suddenly appeared sometime in the last year to year in a half. I blame the fake celebrities (Kardashians, Hiltons, Jersey Shore kids).

While it's not an overused phrase, my ears hurt every time I hear someone say ain't. Here in my little corner of southwestern Ohio, it's used often.

How about off? As in "kill off" – why can't we just kill things or let them die? Must they now die off – presumably from feeding off of oil-contaminated food in the Gulf? Can't they just die from eating contaminated food? Wish people could get off tossing off into every other phrase. Well, enough for now, off to bed.

I just had my comment deep-sixed — or perhaps offed — by my new mouse. Pardon me while I disable a few functions.

My current peeve is "Have a blessed day," which I fervently hope is endemic only to the South, along with open Bibles on dashboards. Can you say "ostentation?" (There's one from about forty years ago: "Can you say…")

However, anent "People used to wait for other people and have conversations about things. Now they wait on people and have conversations around things." Doesn't that pretty-well describe interaction in our increasingly superficial society?

I meant to add that, back in the paleolithic, my CB handle was "Galloping Curmudgeon."

When I worked for US Bank back in the 1980's "leading edge" was in vogue. NOBODY says that any more.

The one that really irritates me is "Quantum Leap" which people use to mean some large or grandiose change. In actuality a Quantum Leap is completely the opposite; infinitesimally small – used to describe the changing of an electron from one orbit around an atom to another level. Whenever I hear it I want to yell "It's an incredibly SMALL leap, dumbshit!"

Anyway, your post was really "out of sight".

My twenty-something son asks, "Do you feel me?" And I recoil everytime. What the hell?!

And what about the fact the everyone is going to "try and" do something? It could be an accepted usage, but I think it much more precise to "try to."

Julie Z, some things I never get tired of hearing.

Open bibles on the dashboard??? REEEAAALLY? Is that in place of an airbag? I hate the thought that my airbag won't save me from a person with an open bible on the dashboard. No, I've never seen it. Then again, Oregon has the distinction of being the "least churched" state in the union.

Leading edge gave way to pushing the envelope. And I'm not a real scientist, but I think quantum leaps are mainly discrete. Large or small is sort of a matter of perspective. Relativity, and all that. Somebody please gallop in and correct me.

BTW I may not be a real scientist, but I know way more than John Boehner.

Sick post, DUDE!

Never said groovy and all that. Never the bomb for me, even in the 60's.

John Boehner is MY state rep. We're trying (desperately) to get rid of him. Unfortunately, my little corner of Ohio seems to adore him. If we oust him, it will be a miracle. Maybe we need some of those dashboard bibles.

As a former English teacher I feel your pain! However, what REALLY bugs me is that no one seems to understand the difference between "your" and "you're", or most annoyingly, "its" and "it's" anymore.

I feel you're pain. Its so sad bad grammer exists. Get it?? Get it??

My biology professor in college used to like to use the phrase, "That's a really good question." when he was stumped. The next thing he'd do would be to assign that question to the questioner to solve. That's how we discovered that no one really agreed on what the formation of parrot fish beaks was (in 1989 anyway). So I guess I'll never know if the beak is made of keratin or is formed from the fusion of the front teeth.

Here's another one. My son had his iphone stolen. Poor child. I had to go to the store to pay for the pre-order- he only had CASH but ATT wouldn't accept case. While there, I commented that I'd never heard of a store which didn't accept CASH… so the manager proceeded to explain to me that cash is only good for immediate purchases, anything pre-ordered can't be paid for until the order is fulfilled, so you HAVE to use a credit card. Then he added "Cool beans?"

I was with him up to that point. I said "Huh?" My son flamed in embarassment "Mom I say that all the time!" I replied "Perhaps but since you don't speak to me, I don't know that one!"

Everyone was sufficiently convinced that the old bat had her say and we moved on. Whatever happened to the good old far-effing-out, man! Cool BEANS??

(sorry, ATT wouldn't accept casH, in any case.)

Thank you for discerning this perfect storm of shifting paradigms.

I've heard this conversation several times: "She's all [fill in the blank], and then he's all [fill in the blank], and I'm all whatever."

Huh. I've heard cool YOUR beans. I don't think I have any beans, but it could be a case of mistaken derivation. I love what Dave Barry said about apostrophes: they're to let you know there's an "S" coming up in the word.

This is one of the best essays on modern language that I have read. It's just so cool!

My current pet peeve is the use of "actual" or "actually" throughout any sentence, whether it actually applies to the actual thought or not.

"Thank you for sharing."

"Thank you for sharing."

I've heard this conversation several times: "She's all [fill in the blank], and then he's all [fill in the blank], and I'm all whatever."

(sorry, ATT wouldn't accept casH, in any case.)

Like, this was really, like, fun to read? Ya know, like, nice, and stuff.

Dang, Frank! "Slightly different Senator" would have been so much funnier. Servers here think our choices are "awesome" or "sweet." Or excellent. Any way you put it, I am apparently the maestro of the menu.

Way extreme post. Yo.

I used the word, groovy, not long ago. I beat myself afterward.

Someone once said that when you hear, "That's a good question," you're about to get a lousy answer.

Do all servers etc in your area proclaim whatever choice you make as excellent? It's big here — or was several days ago.

I have a dear friend who recently, when I'd tell him some tale of woe, would say, "Sorry about it." I wondered where on earth his 60 year old brain got that, until I heard him talking to his 28 year old daughter and he told her something to which she said, "Sorry about it."

For a while, everything was "cool" and when you'd say something unbelievable, you'd hear, "Dude!" I'll never forget the first time I heard a respected nurse practitioner friend of mine use it as I was telling her something crazy a patient did. Made me want to rub my eyes and make sure it was her standing in front of me.

Fun post Murr!