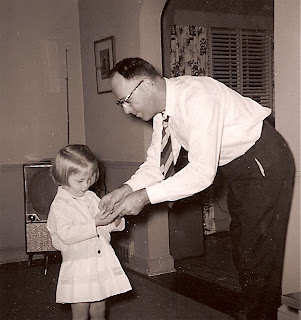

My daddy knew everything. You could ask him why the sky was blue or why the leaves turned colors or what the name of that mushroom was and he would tell you, right down to the wavelengths and the refraction and the chromatophores and so on. So when I asked how you could tell a boy baby from a girl baby, and the whole room tensed up, I didn’t really notice. I was pretty sure he had the answer. Just that right then wasn’t a good time.

It was easy enough to tell boys from girls at my age because of the clothes and haircuts, but little babies all looked alike. I waited a day or two and then, since I still wanted to know, I asked again. Mom cut Daddy a glance and discovered something urgent to do in another room, and Daddy pulled the drawing paper out of the secretary and got a pencil. He started to draw and explain, but with none of his usual vitality. The salient feature in his illustration–in profile, as I recall–was what he called “a little flap of skin.” I looked at the drawing and suddenly remembered how you could tell a boy from a girl, and also that I probably shouldn’t have brought it up.

In my defense, at that point I didn’t have a lot to go on. My only brother was seventeen years older than me and out of the house. Dad was the sort who buttoned the top button of his pajamas. I didn’t have a lot to go on, but I did have Danny Hall.

Danny Hall was the inordinately proud owner of the first little flap of skin I ever saw. He had made a point of showing it to me not that much earlier. It was a curiosity, for sure, but I had no idea what it was for, and hadn’t made a connection with that whole boy/girl thing. As far as I knew, it was just something that Danny Hall had. He was always coming up with stuff. I do remember he was interested in what was in my pants, but that struck me as odd. I didn’t have anything in my pants, not that you could point to, or with.

Besides, as gullible as I tended to be, I was getting to the point that I didn’t trust Danny Hall that much. Even if you couldn’t figure out what he was up to, you could be pretty sure it was no good. That same summer he had found a plain white rock and he held it out to me and told me to lick it. Even though I hadn’t figured out it was a petrified dog turd at that point, I didn’t lick it. Because why would I lick a stone? Especially one of Danny’s stones.

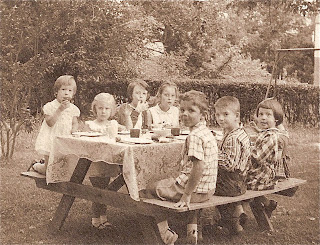

The Halls lived on the end of the block, and they had a giant mimosa tree that was gorgeously climbable even to abbreviated sorts like myself. We used to play over there a lot; we had to make up our own games, because plastic and electricity hadn’t been invented yet. It was a wholesome time. So mostly, we played World War Three. This involved a lot of hiding behind bushes and spying and such. That’s what we were playing when Danny lobbed a brick way up into the air and it came down on my head, and don’t think I can’t still show you exactly where it landed. I wasn’t much of a crybaby but I screamed bloody murder. The closest grownup, unfortunately, was weird Mr. Balderson, who snatched me into his kitchen, clipped out a bunch of my hair and began boiling washcloths and applying them to my head. By the time my mom intervened, I was still bleeding, newly scalded and hadn’t stopped bawling. Danny Hall was apprehended and brought in to defend himself, squirming in his closely-gripped shirt. He had a defense, all right. “I yelled BOMBS OVER TOKYO!” he protested, all innocence.

So back to Danny’s penis. Danny’s penis reminded me of nothing so much as one of those little valves you blow up a vinyl inner tube with. I didn’t say that out loud, which, in retrospect, was probably a good idea, because Danny was the sort who might have sensed an opportunity. Anyway, it was his flap of skin that popped into my head when Daddy drew his somber little picture. I got it right away. I wished I’d asked him about the phases of the moon instead.

I didn’t keep track of Danny. I did hear, later, he had become a hoodlum. Much later, I heard he had become a lawyer.

Vivid story, wonderfully written. I can imagine having been there!

Very well written and the pictures were great. It takes me back to the things kids do and there seems to be a Danny Hall in every neighborhood. Thanks for sharing.

This reminds me so much of my own childhood; same question to my dad, same belated realization of where it was leading; and, yeah, I had a Danny Hall too.

Great essay.

I'm laughing out loud in a public Starbucks over "just something that Danny Hall had". Very hard to explain to the other patrons… 🙂

What a hoot! I think my HUSBAND is Danny Hall. Except his name is different. But same little flap, and he'd love to get me to lick some petrified dog turd. Funny man. Funny Murr.

All is not lost, I still have Murrmurrs to lighten my load. Your the best.

Loved the part about your dad. I remember the day, about age 11, when I came home after ice skating at the neighbors' pond. I had heard an older boy call another kid something I didn't understand, so at the lunch table I asked my dad what "jerk off" meant. He turned beet red, stammered something vague, and never did quite answer — but I sure got the message that this topic was verbotin. Oh, and about that wholesome ice skating pond. It's where I heard and used my first curse word, smoked my first cigarette, had my first French kiss, and saw my first naked boy (a skinny-dipping delinquent who jumped up out of the water, very briefly). Yikes, who knew they had HAIR down there!?!

You can't imagine how much information I was lacking. And when someone came up with the real story, it was too implausible to believe. It still seems a little wacky.

The family word for Down There (as it was in my distant youth) is "peep." Dear 3-yr-old granddaughter Oona has become locally famous for her commentaries on the subject: Boys have hanging peeps.

My version of Danny was Gerald; a proper little creep he was too.

Loved the photos, of course, and am still chuckling. Perhaps Danny Hall will re-surface as a result of your blog. Don't be surprised.

My Danny Hall was called, appropriately, Dennis Dick..and he had me chanting Father Uncle Cousin King for days til someone told me what it really meant! What a little dickhead.

@SylvanB: we didn't have a family word for "down there." "Down there" was the naughtier schoolyard version of That Which Shall Not Be Named Because It Doesn't Actually Exist. As far as anyone in my family knew, we were all smooth Down There.

@Susan: Dennis Dick? Really? Whoa.

A great anecdote, and I love the ending about hoodlums and lawyers whether it was true or not. 🙂

Oh, my family was very progressive. "There" was generally referred to as "your Underneath." As in, "did you wash behind your ears, and your Underneath?" Seemed perfectly reasonable to me.

Hi Murr–thanks for stopping by my blog.

My, how did I not get around to reading yours sooner–maybe I haven't on account of hysterical laughing that would accompany my reading.

This story is a hoot, and a classic all rolled in one.

Well, I'll be back.

GREAT story! On KGMom's heels, thanks for stopping by. This is very funny and the photos suggest we are most likely the same age, give or take a few years. What this put me in mind of was this: My daughter is 6 years younger than her brother and from birth until about 3 years she was the proud owner of a very pronounced umbilical hernia, that did eventually tuck itself back in as she grew. One morning when she was 22 months I walked in the bathroom to find her standing in front of the toilet, carefully aiming her belly button in that direction and simultaneously piddling down her leg. I exclaimed, "Abby! What are you doing!?" and she turned to me, beaming, and announced, "I pee yike Dan!" Later, in graduate school as a psych student, I was taught that all girls really want that little flap of skin. Experience suggests they can be a wonderful but messy nuisance at best and at worst, the hallmark features of hoodlums and lawyers. Thanks for the laugh and the visit!

A delightful walk down into childhood!

Thank you. Your Dad was very funny.

I also enjoyed your pond visit.

Looking for frog spawn here in the mid-west!

Happy March,

Sherry

That is lovely writing. What a shame about Danny and that he turned out so badly after all!

🙂

Hi Murr, peeping in to say hi, love your writing. Found you from a comment on Postman's blog. Hi there! Olivia

Oh — this reminds me too much of my awkward childhood. No — I can't get started on that.

You are a delight.

Vivid story, wonderfully written. I can imagine having been there!