I have mealworms. Let the seduction begin.

I have mealworms. Let the seduction begin.

I have mealworms, two industrious chickadees, and a box of beebling baby birds at the goober stage, all ready to assemble. Marge and Studley Windowson did find the mealworm stash near the suet feeder on the other side of the house, or someone else did, but still I yearned for intimacy. I did not want to attract scrub jays. I gave it some thought. The mealworm store lady probably couldn’t guess how much time and care I was willing to devote to this project. I cracked open the window close to the birdhouse. When I was certain only my chickadees were around, I eased a worm out onto the windowsill. Nothing happened. But when I turned my head for a moment–okay, I went to the toity–it was gone.

The next day I edged my palm out onto the sill with a mealworm in it. Studley definitely saw it. Studley definitely wanted it. He made feints at my hand, hovering. Then he landed on the sill, weighed his responsibilities against his fear, stabbed at the worm and rocketed off like he’d swatted a tiger’s nose on a dare. A half hour later he was landing on my finger. Then on Dave’s finger. On two hearts at once.

The next day I edged my palm out onto the sill with a mealworm in it. Studley definitely saw it. Studley definitely wanted it. He made feints at my hand, hovering. Then he landed on the sill, weighed his responsibilities against his fear, stabbed at the worm and rocketed off like he’d swatted a tiger’s nose on a dare. A half hour later he was landing on my finger. Then on Dave’s finger. On two hearts at once.

They say there are wormholes in space-time. Portals to other universes. I was already smitten, but it wasn’t until the next day that my entire soul tipped into that gravity well. I was outside weeding and stood up to stretch, and there came a flibbet of wingbeats, and there was Studley, on a twig eight inches from my face. He tilted his head, back and forth, sent me one bright black eye, then the other. And I fell through the mealwormhole into Studley’s world.

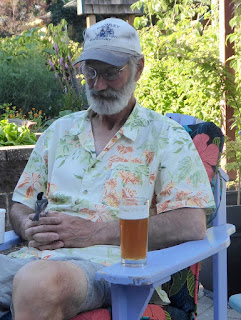

I wasn’t anywhere near his window. And I was wearing a hat. But he knew me. Had he been looking at me for years, even as I was looking at him? He’s paying attention, that’s for sure. Dave stands in the garden with his hands relaxed at his sides and a small grown bird tucks into the cup of his fingers. I get out of my car and a bird lights up the closest branch, and dips over to my hand, his feet as important and small as punctuation. He doesn’t weigh any more than a held breath.

I wasn’t anywhere near his window. And I was wearing a hat. But he knew me. Had he been looking at me for years, even as I was looking at him? He’s paying attention, that’s for sure. Dave stands in the garden with his hands relaxed at his sides and a small grown bird tucks into the cup of his fingers. I get out of my car and a bird lights up the closest branch, and dips over to my hand, his feet as important and small as punctuation. He doesn’t weigh any more than a held breath.

Marge hasn’t taken the plunge. That’s okay. I worry about habituating Studs to people, although he’s only stalking Dave and me, but he did land on neighbor Anna’s teacup. It’s white, just like the ramekin I carry mealworms around in. Maybe it’s because I’ve zoomed in on so many photos of Studley, but even now, when I see him through the window, he seems larger than he really is. Substantial, even. He’s not. He wouldn’t tip a scale with a peanut in the other pan. He is a tiny, tiny bird. But he’s smart.

Marge hasn’t taken the plunge. That’s okay. I worry about habituating Studs to people, although he’s only stalking Dave and me, but he did land on neighbor Anna’s teacup. It’s white, just like the ramekin I carry mealworms around in. Maybe it’s because I’ve zoomed in on so many photos of Studley, but even now, when I see him through the window, he seems larger than he really is. Substantial, even. He’s not. He wouldn’t tip a scale with a peanut in the other pan. He is a tiny, tiny bird. But he’s smart.

He’s damn smart. He’s probably known me for years before discovering I’m useful. When I’m too slow to get him a worm, he knocks the hat off my ramekin and helps himself. He goes off to a branch to subdue it for a baby’s gullet, whap whap whap. When we call it a day and go inside, he figures out where we are in the house and hovers at that window.

He’s damn smart. He’s probably known me for years before discovering I’m useful. When I’m too slow to get him a worm, he knocks the hat off my ramekin and helps himself. He goes off to a branch to subdue it for a baby’s gullet, whap whap whap. When we call it a day and go inside, he figures out where we are in the house and hovers at that window.

He knows when beer-thirty is.

I know what he likes me for. But is it love?

I want to get this right.

The sober voices say all love is self-interest. The sober voices are measured in their assessment. They manage risk. Keep their own hearts on a short lead, safe from disappointment.

I choose headlong.

Because I don’t know just where a love story begins. But maybe love is the name of the charged ether that joins our worlds. I do know I’ve got the trust of the smartest, bravest, most valiant chickadee in the whole world, a world that can be frantic, and grabby, and barren. Does he feel a lift in his little gray chest when he sees me? Does he love me too? It might not matter. I’ve got enough love for both of us.

Because I don’t know just where a love story begins. But maybe love is the name of the charged ether that joins our worlds. I do know I’ve got the trust of the smartest, bravest, most valiant chickadee in the whole world, a world that can be frantic, and grabby, and barren. Does he feel a lift in his little gray chest when he sees me? Does he love me too? It might not matter. I’ve got enough love for both of us.

Pin lovingly fashioned by Amy Weisbrot, amyweisbrot@gmail.com

Murr, this brought tears to my eyes (the good kind). Not only can you wax humorous, but you can express the stunning beauty of acquiring the trust of a small bird. Beautiful!

I always figured Studley was special. Thanks.

"He doesn't weigh any more than a held breath". I loved that description. Even though mealworms are involved, the way Mr. Studly comes to your hand or perches on your finger is magical. The video was so enjoyable. I liked hearing Mr. or Mrs. Studly's bird calls for you.

Chickadees usually grab a seed and fly off to a branch to work it over. Every now and then Studley grabs the worm and waits for a few seconds to look me over. Of course, he CAN pick up more than one worm at a time, so…

So very happy for your moments of utter delight in the friendship of Studley. In that connection, there is no pain, no injustice, no ranting idiot telling lies. Bask. Bask with worms and birds, and a spouse to share it with. What could be lovelier?

Studley,

Thank YOU for sharing your friendship with a human being who does so much to make this world survivable.

P.S.Where do I get mealworms — are they live or freeze dried?

I got mine at the local Backyard Bird Shop, but you could get them at any pet store, I'd think. These are live and you keep them refrigerated so they don't think about turning into beetles for a while.

You can grow your own too. Let some turn into beetles and keep feeding them. They will make little grublings.

We'll see what happens. If Studley hangs around all year (I don't know if he does or not) I won't be able to get anything done outside.

How absolutely lovely! The relationship and the telling of it. Thank you for just making my day a lot brighter and better.

We need that these days. I'm very grateful to the Studs for lifting me up.

Wipes a tear. Beautiful, absolutely.

Did you see the toes, Bruce?

Wow!!!! I need to try the mealworms on my windowsill birds, although they still look like bait.

Let us know what happens!

Wow! You did a great job with the D's, and with the blogpost. To keep the series going, maybe write the next one from the mealworm's perspective?

That totally IS what I'd do, but I won't.

The chickadee whisperer! As long as it doesn't poop in the beer.

Yeah, I keep a close eye on him when he perches on the glass. Turn around, Studley. Turn around!

Awwww! So much here to love 🙂 Kinda makes up for those stand-offish crows, dunnit?

I am so over them. There's a new kid in town.

Yes. Yes. And yes.

This privilege always but always makes me smile so broadly my face hurts.

I am so glad that Studley took the plunge.

He's a dang tonic.

Oh swoon oh melt. You have the connection. I love this and you.

I knew you would!

Beebling babies. That is exactly what they sound like. Thanks for this special love story.

Update: Studley and Marge's babies flew the coop on the 11th. They've been hanging out in local trees, still being fed, of course, and then no one was around for a couple days. But yesterday Studley was back! I have no idea where they went.

You have outdone yourself, both in making friends of these birds, and in writing about the process. Thanks for sharing.

I will use you as a character witness when I'm arraigned for strangling my neighbor's cat.

Wonderful! Both the love fest and the telling of it! Totally made my day…probably my year!

Thanks! Mine too.

A small tear in the veil between worlds

Nice.

A chickadee once perched on my outstretched hand and ate peanut butter from my palm. Your love affair with Studley leaves me breathless. (sigh…)

PEANUT BUTTER???

They stay here (British Columbia) year-round, and peanut butter is packed with the calories and nutrition they need to survive. I was refilling the feeders and suet logs but he was impatient so I scooped a spoonful of p-nut butter into my palm and he sat on my finger and scarfed down the entire thing. That was 1976 and I'm *still* thrilled to bits.

I love every word of this and played the video twice. I'm so happy my eyes are leaking, I have a grin wider than my face. Maybe love isn't a word in the bird world, but Studly Stanley definitely shows appreciation and trust and that's the same thing in my book.

I've got the same book.

When I was in London, at Hyde Park, I met a man who was feeding birds from the palm of his hand. Jim told me he came there on Saturdays and Wednesdays and had for years. He filled my palm with seed and a dozen or so Great Tits and European Robins gently landed and dined. The memory of this still makes my heart happy.

Studley will land on any of my friends if they're around me too. Although not as often if there's no mealworm forthcoming. So your friend softened the world up for you. Excellent!