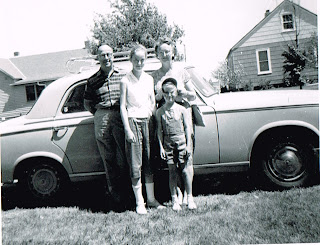

Dave and his sister are two years apart in age, and I used to watch them reconstruct their childhoods like two kids knocking each other’s Tinker Toys down. “Remember when you broke your leg that time you fell off the horse at Uncle Ed’s and cried for three days?” she’ll start out. “That wasn’t my leg, it was your arm, when you tried to hand me a box of hornets when we were camping in Alberta and you tripped over the moose,” Dave will counter, and all the while their mother would stare at them as though they had fallen out of the sky and not out of her. Neither child had ever broken a bone, they’d never been in Canada, and they didn’t have an Uncle Ed. There’s no good anecdotal evidence they ever were in the same place at the same time, and if they didn’t both have such a strong genetic ability to make shit up, you’d never guess they were related. Still, at least they’re coming up with something. My memory is gauzy at best.

Odd things percolate to the surface from time to time but I have no conviction they ever happened. I tend to remember my humiliations. There were a bunch of years I spent humiliating myself but, in what is no coincidence whatsoever, I’ve blacked most of them out.

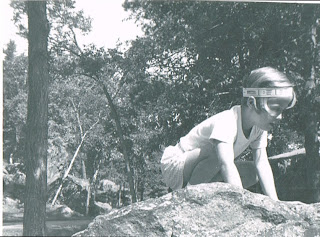

Sometimes I think I remember something because there is a photograph of it. The photo either makes it easier to hold onto a memory, or I’ve concocted a story to go with it. Most of the things I remember aren’t very important. We might have gone on a terrific vacation and seen monuments and waterfalls and splendors, but all I recall is watching Daddy strap an oiled tarpaulin over the suitcases on the roof rack of the Peugeot. Or I’ll remember the knotty-pine interior of the motel rooms, where he always insisted on testing the mattress for firmness before shelling out the $14, but never rejected a room. Or the gift shops with the postcards of chipmunks, the critters made out of pine cones, and the itty bitty birch bark canoes. I have one photo of a day I do remember. I had found a feather and a headband and I belted my raincoat tight and crept around the landscape. I was certain that other people in the parking lot thought I was a real Indian because of my plaid raincoat and great stealth.

|

| Stealthy Indian at the right. |

But if something hops up and down on one of my memory neurons, there’s no telling what’s going to bubble to the surface. That’s because, like many in my generation, for a lot of years I don’t have memories. I have flashbacks. And that’s really pathetic. Flashbacks are memories of things that didn’t even happen. We are each the author of our own life, and I don’t know if mine is fiction or memoir.

In fact, there are about fifteen years there when just about all I can recall is buying the next pitcher and sliding a quarter onto the pool table. Not a lot else comes to mind. Which, come to think of it, is probably a thorough accounting. If I’d had any foresight at all, I would have hung out with sober people so there would be a repository for my memories, even if it had to be in someone else’s brain. But those people didn’t like to hang out with me.

Oliver Sacks discovered that music was entwined intimately with the gooey memory portion of our brains. People who had been catatonic for years came alive and began to dance when the music of their youth was played. Some day my peers and I will be sitting around unresponsive in an institution and a future Dr. Sacks will get a wild hair and blast out “Gimme Shelter” from the sound system. We’ll all dance, all right, but we weren’t in the Cotillion set. The good doctor will think we are having a seizure.

I love this post. My memories of sporadic moments in my childhood are all in black and white photos. It's as though my brain simply erased those memories somewhere along the road to adulthood.

Wouldn't it be nice if the real reason we can't remember anything is because we are cleaning out our heads to put shiny new stuff in? Yeah, as if.

Forwarding to my siblings who have always accused me of making everything up. Perhaps….

They could very well be right, of course.

Fuzzy memory seems to effect a lot of us, especially those up in Washington, D.C. that is. Must be something about the place. I never did much of the kind of stuff that gives you those flashbacks, but I can't remember crap, especially people. But I remember every single thing I ever did with music and every animal encounter, and there were hundreds of those. Oh well, thank goodness I can remember how to get back here and read your fabulous posts. Have a great weekend Murr.

You have a very tasteful selective memory. I approve. I wish I could remember music I learned, but the mental tape is erased a month after I quit playing a piece, even if I had been working on it for a year. I do regret that.

Being told something often enough can turn it into a memory … at least that's how I account for the perfect 'recollection' I have of my older sister handing me an apple from our backyard tree while we stood under it in snow. Only problem is, I was 2 at the time …

I once looked at the oval figure carved in the back of Mom's oak rocker and realized I had spent a lot of time staring at it–when I was being rocked as an infant. That has to be my earliest memory.

How perfectly lovely.

My brother, two years younger, has pretty much the same memory as I of the same event. My sister, ten years younger, lived an entirely different life during the same event. As she should have, being of a different generation.

I am five, sixteen, and seventeen years apart from my siblings. I don't think we had the same experiences at all. Once when we were all adults, and I said something a little provocative to my (tired) parents and they shrugged "whatever," my oldest sister turned to me and said: "you've done wonders with Mom and Dad."

I think I blot out the bad stuff, and the good stuff keeps getting better. In another ten years my used to be a 15 handicap will become I used to be a scratch golfer.

Hang reality. You have a very sound life strategy, there.

I read all of your posts, Murr, but usually I cannot think of a thing to say that doesn't sound inane. But since I just finished reading Oliver Sack's book about Hallucinations, which includes the way memories work, I can finally say, "Yeah! I have memories of things that didn't happen, too!" 🙂

This gets dangerously into the question of What Is Reality. Fortunately, the answer doesn't really matter!

Joeh can't be right. The only memories that come back frequently, and very clearly, are the many times when I did something stupid, made an ass of myself, and, of course, the bad parenting moments. Those beat me about the head and shoulders on a regular basis.

And for those moments, I, Murr Brewster, personally forgive you.

Ah, the old "False Recovered Memory Syndrome." We all have it, I think. But we accuse our daughters of being pod children when they come up with memories that we have NO memory of.

Loved this post!

Um… Would those memories be ones in which you do not come out good?

I'm glad I'm not the only one with a crap memory. When my siblings and I get together, we usually end up agreeing that we must have grown up in entirely different households, because we have almost no common memories at all. Though both my sister and I vividly remember the time I hit her in the butt with a lawn dart (yeah, back in the days when they were still pointy, dangerous projectile weapons). Funny how some things leave a lasting impression…

Oh, lawn darts. We had those but my parents (wisely) took them away after I discovered my sister posing my brother in front of a dartboard target hanging from his bedroom door. He must have been a stupid child. He was standing there so she could throw the lawn darts to make an outline of his head and body.

Were they called "jarts"? Faulty memory is throwing that word into my mind.

Jarts it is. You all are younger than I am, but I love the fact that you're old enough to have been given lethal toys. Your brother, indeed, should have been either culled from the gene pool, or beatified. And Diane, I can well imagine the particular lasting impression that lawn dart made!

Saint Jart. Now available as a boffo confirmation name.

I hope the kid's name was Art. Then he could be Saint Art of Jart.

This comment has been removed by the author.

I went on those same family vacations, Murr. Except our car was a Rambler station wagon, and everything fit inside. Whatever happened to knotty pine, anyway?

We both got our kicks on Route 66! I think after Dad ditched the Studebaker with the suicide doors for the Peugeot, and later yet for the Volvo, it cemented the neighbors' suspicions that he was a Communist. He might've been, too.

It's simple. The older I get, the better I was.

Ah. My story is either fiction or memoir, but yours is a fish story.

Ahh….memories. My mom used to let us 4 kids parade around the house banging on pots and pans with wooden spoons. Her friend observed "how can you stand the racket?" Mom said "it's a happy noise and at least they aren't off somewhere torturing each other."

Our kids love the stories of when we DID torture one another, like when my sister and I (we were older) got tired of our brothers' crap and tied them to trees in the back 50 acres behind our house and left them there for awhile to ponder the sin of being Younger Pesky Brothers.

I hope you told hem tales of peg-legged marauders while you were at it.

Happy Birthday, Mick Jagger!

Whoa, gimme shelter! Seventy?

Oh, I can relate to this! I almost wish I could blame my bad memory on aging synapses or post-adolescent substance abuse, but I've always been this way. Sure, I can beat the crap out of you at Jeopardy, but my personal memories are like sitting in a dark room where a mime is performing, and once in a while someone throws the switch and illuminates the action ever so briefly, and then it's all darkness again. Even when I go back through my journals, it's like reading a novel about someone else's life (and a pretty dull one, at that!).

Oh, I had to get rid of my journals. Too embarrassing. I always thought maybe some day I could be a writer, and I sure didn't want any of that crap hanging around.

I am defiantly (not a spelling error) of the opinion that the brain is like a big tub under a trickling tap and once it gets full there is spillage and replacement. (Or, as computers invade my life more and more, the brain is like a hard drive that gets fuller and fuller and eventually nothing new will fit without deleting some old stuff.) That's my theory, anyhow. And I must say, Murr, you may have killed a lot of brain cells but either you're busy manufacturing new ones or you had a whole lot more than the average person to start out with 🙂

One of my favourite movies was Awakenings, based on Oliver Sacks' memoirs. Amazing story.

Isn't it? And he is quite the oddball himself. That might be why he got interested in such stuff. Thanks for your kind words, by the way.

I always wondered if my earliest memory – I was holding my mom's hand, walking through the trailer park on the way to see my babysitter, Lettuce – was made up. I was 30 before I mentioned it to my mom, and she told me I was two years old and the babysitter's name was Gladys. She didn't know I thought her name was Lettuce. The Lettuce/Gladys thing convinced me it was a real memory.

Absolutely! And LETTUCE! Start writing novels, honey. You've got all the raw material.

I remember bits of places. The trees and moss on a particular cliff. The moonlight on our living room rug. The lower branches of the Christmas tree in the hospital lounge. A bed made up in the slanty space under the stairs in the nurses' residence. The warm spot beside the smokestack on a boat. The porch of a house in farm country, with an old wooden swing.

How I got there, or what I was doing, or even how old I was at the time: all lost.

What I do remember clearly, and with all the condemning details, are the times I took it upon myself to cure my Younger Pesky Brother of the sin of Existing.

I will go ahead and speak for all readers of this blog and thank you for that first paragraph.

I remember things that are of little importance. But things I really should or need to recall? Nope. Nothin'.

I can sit at the keyboard (not this one) and play a few pleasing notes, but when I try to repeat it, maybe only hours later – it's all gone.

But I have a pretty solid recall from early childhood.

Do you? Or do you just think you do? Sorry, only messing with you.

What do you mean it was all made up? I vividly remember being just behind Dave at the camp in Alberta when his sister handed him the box of hornets and tripped over the moose. And I remember him finally coming out of the coma seven days later. What a worrying week that was.

My own memory is just as erratic. I also black out all the humiliations and remember little snatches of things rather than the whole picture. My sister has a photographic memory and constantly embarrasses me by recalling all those faux pas I've conveniently obliterated.

OMG, you're Dave's imaginary friend! Seriously, don't take your sister's recollections to the bank. She could totally be full of shit.

The things I find embarrassing is when something triggers a memory and It sprays out of my mouth regardless of whether it's interesting or a version of, "I remember when that house was blue and a woman came out the door wearing a brown dress." and then? Oh, that's it. No story. No content. Just a random flash that I am compelled to share.

I believe your compulsion has to do with a need to off-load your mental flotsam to take on something new. Too bad your jetsam has to wash ashore in someone else's brain.

I have a lot of memories that are clear as a bell, that go all the way back to the age of 1. I can describe in detail things to my mother that I should not be able to remember.. I am now 62 and they have not dimmed a bit..

However, don't ask me what I did yesterday.

I can sometimes manage yesterday, with prompting. But I can't remember two ingredients between the recipe and the fridge.

I have a lot of memories that are clear as a bell, that go all the way back to the age of 1. I can describe in detail things to my mother that I should not be able to remember.. I am now 62 and they have not dimmed a bit..

However, don't ask me what I did yesterday.

Also Murr. Do you have any idea, why when I make a post here, it shows up twice? Everytime.

I don't have a clue. I thought you were just extra avid, and I appreciated it. Anyone else have any ideas?

I have never been in Alberta. I have no Uncle Ed. Never broke my arm. Does this mean I'm related to Dave and his sister?

No! Cool! You're related to ME! I DO have an Uncle Ed!

Wait! Wow! I have (had) an Uncle Ed too! His name was really Edgar, and he was only 14 when I was born, so he was more like a Pesky Big Brother, and I called him Eggie. And I distinctly remember that I "helped" my grandmother clean his room when I was about 4, and there was chewing gum stuck to the metal bed frame. Three wads.

How did he turn out? Being a boy who didn't have to clean his own room, and all.

I don't know if most of my memories are real or imagined. I am sure the memories are better than the actual happening. But when I think about my childhood and young life none of the memories are great so that must mean that the real happenings must have really sucked.

the Ol'Buzzard

I think you're seeing this wrong. The reason you remember the dull stuff is because it stands out. Your childhood was idyllic.

I have always wondered how anyone would be able to write their memoirs/biography. I can't remember much more than just a few pieces of my childhood/adolescence/adulthood. I can't imagine writing a book about any or all of those times. How do they do it without writing a novel?

My first memory is of being in the backseat of a car, looking out the windows into the dark, searching for a lost dog. Don't remember the dog, just looking for him. That is from age 3.It makes me realize that I have to stick around a few more years in order to ensure my grandkids will have any memories of me.

I don't know. I'll bet if you do something truly wacko, they'll remember you.

I have memories of my early years that don't match anything my parents told me, but then their stories of the same years don't match each other either. There are a couple of confirmable memories, like the time I convinced my brother to climb over the fence with me into a neighbours yard and "help" with the house painting while the neighbour was out and the bath we both had later with turpentine added to the water to get the paint off us.

I am willing to wager that your recollection would have been even more vivid if they had made you sit in.a bucket of undiluted turpentine.

I think the fact that I've been an expat for most of my adult life means that I have frozen certain memories of my past in the USA like mental snapshots that I can leaf through at any time. One of the features of my homecomings whenever I went back to Ohio for a visit was always sitting down for long sessions at the kitchen table with my mother and a pot of coffee recalling anecdotes about all of the most unique people in town from back in the fifties and sixties, like: Remember the time Uncle Bob had that '56 Cadillac that he ended up hating because it was such a lemon and that guy came in from the parking lot and said, Hey Bob, is that your Caddy out there, because it's on fire!, and, calm as you please, Bob said, It's insured…let the sonuvabitch burn!? or Remember when Mr. Earwick down the alley came home from squirrel hunting one day, got out of the car, opened the trunk, took his 20-gauge out, shoved it in his mouth and blew his brains out? Yes! and then his wife came home and found a piece of his skull in his cap lying in the driveway!

And so on…

But then ten years ago my mother passed away and when my sister, brother and I were going through all of the old things that had accumulated in the house where she and my father had lived for 42 years, I couldn't resist the temptation to start rattling off as many of those old stories as I could recall, especially since my brother and I had been working our way through a bottle of whisky since noon, and finally, exasperated, my sister said, "Geezus! where do you get all this shit? And who the hell are all these people you're talking about?!

Things got quiet for a beat or two as my brother and I stared at her a little shocked, and then I said: "Look, Mom and I used to always do this, and now she's gone! So if somebody doesn't do it with me right now, I'm gonna lose it. You're the oldest, so you're elected!"

And that is how a matriarch is born. When we kids were "orphaned" we informed the oldest sibling that she was now the matriarch. That appellation did NOT sit well with her.

Hey Murr! I sympathise. Right now, my breakfast is a mystery. Indigo x

Gosh, Ind, sometimes my breakfast is a mystery when I'm eating it. But that doesn't slow me down.

I've included this directive in my living will:

"Before you unplug me, be sure to put headphones on me and play this: Leon Russell's salute to Little Richard

My new little Device is not coughing up that link right now, but I will say at if anyone were to put headphones on me and play Pat Boone's version of Tutti Frutti, it might kill me. I would die of racial shame.

I have a pretty clear set of childhood memories. Not all of them are things I want to remember, but you take what you get.

You could always add alcohol and see if they improve, or go away.

Since I had no brothers or sisters and am orphan besides, I'm allowed to misremember my childhood in any way I choose.. and I do.

I hope that wasn't a misremembering!

Just a note: When I was teaching a college course on writing, the first week of class I always asked the students to write a brief essay about their first childhood memory. (It was a way for me to get a sample of their un-plagiarized writing.) But the essays were pretty interesting, and I was amazed to learn how many had earliest memories of setting thing on fire, and not things that were ever intended to be burned. Bedding and the like. Weird.

Were you teaching in a reformatory?

Nope. At a Catholic Univ. distance learning site on two military bases. Interesting experience.