At the old cemetery in the Taos Pueblo, I couldn’t help noticing a jumbled heap of crosses and headstones piled up against the wall. The tour guide explained that once a cross slumps over, they set it aside but don’t replace it, and eventually they slide someone else in on top of the unmarked grave. So there’s sort of an expiration date beyond expiration. This is sensible; this helps to relieve density in the thicket of hovering souls.

Beyond that, though, it also speaks to my own suspicion that the value of any dead person changes over time. In general, the deader you get, the less anyone cares about you, until you get really, really incredibly dead, and then you’re interesting again. Which is why the prospect of digging up someone like (for instance) my own mother isn’t as exciting as digging up a certifiably ancient soul, one rigged out with antique tools and funky 6,000-year-old shoes, say.

I bring up my mother because of something I heard on the radio the other day. In some areas of Rumania, people bury their dead and then dig them back up again after enough time has passed to scour the expressions off their faces. And then they clean up Grandma’s skull and put it on the mantel. Something about this appeals to me.

It would be sort of a good-luck charm. I doubt that it would creep me out. For one thing, I would never recognize my mother in skull form. She was too fluffy. Daddy was a little more solemn, but it would still be a stretch. And in either case, there are no skulls to be dug. Our family tradition is to render our dead into a snortable condition and tuck them into a small box.

|

| Me and Great-Aunt Gertrude (life-size) |

On the other hand, I would totally recognize either of my great-aunts. Hell’s bells, they were old. There would be plenty of room on the mantel for their entire skeletons, sitting up. Great-Aunt Gertrude and Great-Aunt Caroline were miniatures. As far as I have been able to determine, they were never not old. Even in the cave paintings, they look a little grisly. Family lore holds that Caroline wanted to marry a Jewish fellow early on, which was unthinkable, so she remained a spinster attending to the needs of her even more spinsterial sister Gertrude until she died at age 104. Sure, they had their fine points, both having been professors at Smith College, but the whole story seems tawdry and nothing for me to be proud of. Although I will hold that the older you are, the more you should be venerated; in fact I feel more strongly about that with every passing year.

|

| Great-Aunt Caroline |

But the veneration thing is always a problem when someone trips over a really old skeleton. These days they can learn so much from one. They can determine what he ate, what he used to clonk what he ate over the head, where he came from, and whether he liked to take long walks along the beach. But no sooner does someone fling him into the air with a bulldozer than some tribe or other starts squawking about sticking him right back in the ground. The land where the skeleton was found either is sacred already or was sanctified by the newly discovered dead-ancester vapors, and the ancestor himself absolutely must not be disturbed. And you can’t work up a good counter-argument because of that whole Christopher-Columbus-and-the-smallpox-blanket thing, the disgrace and shame of which is now installed on the same chromosome as whiteness. It’s vexing.

Because the science of mitochondria has also determined that every one of us can trace our ancestry back to a single miniature woman in Africa, and that means we’re all related to each other, and we all came from somewhere else. What if we were meant to venerate everyone? What if all our land is sacred?

How the hell is that supposed to work?

"What if we were meant to venerate everyone? What if all our land is sacred?" Of course you've just solved the dilemma of the ages. I knew you'd do that sooner or later. Of course some fool would turn that wisdom into a religion and start making up rules with which to control everyone else and before you know it, we'd have another Rick Santorum on our hands.

Ew. Could you have rephrased that?

@ Bill &c…That explains why you see so few Buddhists on Wall Street.

Do you suppose there are ANY?

I love oral "history"…"We were always taught to repeat it accurately word for word, so it is what really happened centuries/millenia ago". Yeah, right. So long as it agrees with my current political position. Of course written history gets the same treatment so what the heck…

I don't know about skulls on the mantel. There are many stories of the wife keeping her husband's ashes on the mantel. One concerns the neighbour lady raising the lid on the box and stirring the ashes with her breath. There, you old fool! That is the blow job you were always pestering me for."

A post-mortem blow job! Snort…a whole new concept of oral history! 😉

I was thinking the Blog Fodder made a good transition there, myself!

Oh, you mean do unto others as you would do unto yourselves? That will never fly, for one thing, there would be no more Republicans….Hey, wait a minute…

I think it's "as you would have others do unto you," but sometimes that's the same thing as you would do unto yourself. If you were really flexible.

Kind of like a dog licking his balls because he can?

I think I'll stick with pictures on the mantel and leave my families earthly remains safely under ground. Wouldn't it be nice though if we could all respect mother earth and each other equally?

That's crazy talk.

I just think it is very cool that if you go back about 100,000 years that we are all African. Funny we don't look it, though.

My people have spent that whole time getting away from the heat.

@Bill and dogs "and before you know it we'd have another Rick Santorum on our hands" … I'm not convinced we need the one we already have.

In my work life I have to do environmental reviews that involve sending letters to local tribes to inquire if they have any objections to the ground-disturbing activities we have planned for one home repair project or another. From time to time they do, and we have to have an archeologist stand by to frown thoughtfully at the shovels as they turn over the dirt, in case any ancestral bones are revealed. None so far. Adds to the cost of the project, the current homeowners are none too pleased, but the potential ancestral bones are protected, just in case.

I can't say how much I love it that a good archaeologist is employed to do that. That is my kind of job-creating.

All land is sacred but only a few of us know it.

In fact, many in power think all the sacred stuff is underneath.

Venerated? All old people should be venerated? Even the drunken bum down on Burnside, collapsing on the sidewalk like a moldy old jack-o-lantern? It's a great theory, but gets hard to apply in real life. But I'm willing to give it a go if the young whippersnappers out there will buy into it also.

And what if all our land is sacred? Where will we put our garbage? Where does the waste from the nuclear plant go? Is high-density housing a holier use of land or would a strip mall be more virtuous?

Good questions. Hard answers.

I don't want to have to dust my ancestors, thanks. And you know sure as anything that grampa is going to get schnockered and knock aunt Betty off the end onto the hearth stone. Does Elmers Glue hold skulls together?

Man, I hadn't thought about the dusting issue. Scratch the whole idea.

Your aunties were miniatures? Um, have you looked in a mirror lately, Murr? The apple hasn't fallen far from the tree.

That's because it can't get up any speed on its stumpy little legs. You long-legged freak. (Love you.)

I may be soon switching over to Confucianism as veneration of the elderly looks increasingly sensible to me.

Ain't it the truth? Looks better all the time.

We have my mother in law on our mantel…really. She's in a box waiting to be scattered. Of course, I would have liked to scatter her when she was alive at times, but DID I REALLY SAY THAT?!?

You have a fabulously skewed mind. It's to be, well, venerated.

I'm venerating it in a beer sauce right now.

I love how you got from there to here.

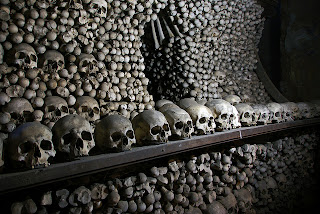

Have you been in the catacombs in Paris? Skulls as art, I tell you. Art.

Catacombs. No. I heard about some cathedral in Eastern Europe that's just about all made of skulls and bones. It's gorgeous. I wonder if I'm mixed up? I mean, what are the odds of that?

I was never a good Aunt and now I am a Great Aunt. Does this mean I should be venerated? I am not going to hold my breath waiting.

I'm a Great Aunt too! I have a so much better chance at excelling at this than I would have as a mom. Personally, best beloved, I venerate you.

Your aunt resembles my aunts except mine were more 'fluffy' except for Aunt Francis. She had a good sense of humor just like her sisters. I think I would like their skulls on my mantel.

See? It is appealing. Uh, you know, to a certain kind of mind.

Your great aunt Gertrude looks an awful lot like my Grandma did, right down to the hat, handbag and coat. You were a cutie! Wonderful pic, Murr. I'm all for venerating our oldsters, particularly as I'm nudging steadily closer to that state myself. As a gardener, I'm doing my bit for venerating the land. All organic and with the happiness of bees in mind.

I think if you keep happy birds and bees in mind in all things, you won't go wrong. Oh. And your cats indoors.

What kind of eleven letter is spinsterial? Did either of them teach social work by any chance? I had a great aunt Gertrude. She always cleared your plate before you could finish your food.

Um…I think they taught English! And hey, spinsterial is a fine eleven -letter word. At least, now it is.

As much as I like the idea of 'venerated', I don't see kids today venerating anything except their iPods.

I'd venerate me an iPod if I had one.

All this talk of deathifying is causing me concern. For years I've told the family that when I croak, just take me up to the 610 bridge and dump me into the ship channel. If I died tomorrow, that is my last remaining instruction.

I need to get this straightened out.

It's not a bad plan. Being staked out for vultures is another good possibility.

So, since I'm 50, does that mean that I'm ready for semi-veneration? What about when I'm 70? Can veneration be pro-rated? Because I'm having trouble getting my 13 year old to think anything I say is even relevant. So where does veneration fit into that?

Just wondering.

I think you've got it exactly right. Veneration is pro-rated by definition. It's just that thirteen-year-olds are not the engines of veneration. But if you raise them right, they'll feel crappy about it for the rest of their days, and you can't put a price tag on that.

I think the popularity of Facebook absolutely proves our succession from a single ancestor. As for veneration for the dead. I have never been to either of my parents' graves and quite honestly I'm not sure I even know where they were 'laid to rest', as it were.

Mine are in Bozeman, and I haven't visited them either. But I adore them almost on a daily basis. As far as I can tell, my father only got one thing wrong ever. And he might have come around eventually.

Bozeman? I don't know enough about you, clearly! I'm a Billings girl, transplanted to MN.

My folks retired to Bozeman from Arlington, VA and got a whole 4 and 5 years out of it before dying. They wuz robbed. I never lived there.

"My people have spent that whole time getting away from the heat."

LOL! Mine too, Murr, and getting paler and more uptight by the mile.

I know. We ain't attractive, but at least we own everything.

Crikey, but I like you–your refreshing sensibility is done justice by your writing (this alone–"this helps to relieve density in the thicket of hovering souls"–has delighted me inordinately today). I like this post so much, I want to share it with other dark-minded randoms in my life. Ah, beware the random traffic I might send your way.

Random dark traffic is my very favorite kind! Okay, I like it all. Thanks!

I've been to the Kutna Hora Bone Church (Ossuary) outside of Prague – both macabre and artsy, which means it attracts all sorts of tourists. Wouldn't you think there would be at least one Ossuary Theme Park in the USA?

There is that Creationism Museum somewhere that gets pretty fanciful. And I'd LOVE to see that Bone Church.

I guess I shouldn't travel anymore because all the monasteries that only kept skulls ( due to a space deficit)are blending together. Thanks for reminding me, I'll look like your Auntie someday. I'm off to eat more icecream now.

That's my plan, too. BTW, what is that doohickey next to your name?

Great post! Very thought provoking. 🙂

Dead people and poor people have lousy lobbyists.