We were just treated to a rare celestial event here. It had been predicted, and although the details of how such a thing comes about are well known to science, the casual observer could be forgiven for succumbing to awe. We’d heard about the phenomenon, of course. But until you see it for yourself, it’s easy to dismiss. Nevertheless, sure enough, right on cue, the skies began to darken, and we all looked up in joy and wonder.

We were just treated to a rare celestial event here. It had been predicted, and although the details of how such a thing comes about are well known to science, the casual observer could be forgiven for succumbing to awe. We’d heard about the phenomenon, of course. But until you see it for yourself, it’s easy to dismiss. Nevertheless, sure enough, right on cue, the skies began to darken, and we all looked up in joy and wonder.

Yes. Water was coming right out of the sky! Just a little at first, bearing its fine mineral smell, the fragrance Life dabs behind its ears. And then a little more. By morning there was visible wetness all over everything. According to official records, this used to happen all the time. But fifty-seven consecutive days of unrelenting brightness has a way of frying the memory tank.

In fact, those same records show that sky water is a frequent visitor in these parts, to the point where people get impatient with it, and wonder if it will ever pack up all its crap and leave, but all that sounds like fake news now. Every day for the last two months, that searing ball of inevitability has barreled across the sky unchallenged, spreading mandatory cheer into the darkest crevices, more cheer than is good for us.

But Sunday it rained. Lord do love a duck. Snails are racing! Ants are excavating! Leaves are putting on weight!

But Sunday it rained. Lord do love a duck. Snails are racing! Ants are excavating! Leaves are putting on weight!

Which, naturally, puts me in mind of stomata.

Stomata, or stoma pores, are my Spark Science Fact. You birders are familiar with the term “spark bird”–that would be the bird whose sheer stunninghood first sparked their interest in seeing even more birds, and consigned them to a life of nerdy clothing and gear and dangerous driving habits. My spark bird was the Western Tanager. I’d presumed that 90% of birds were indistinct and brownish, and then my brother put a Western Tanager into his binoculars for me and made me look, and that was that. WHEN, thought I, did they start making THOSE? What else might be out there?

My spark science fact also changed everything. I was in tenth grade Biology, a required class that I had been dreading since first grade, when I first heard I’d be compelled to slice up a live frog some day. I hadn’t heard of menstruation yet so this was the biggest horror I thought I’d ever have to face. But there I was in Biology class and Mr. Kosek was teaching us about stoma pores. Which was one of the coolest things I’d ever heard of.

My spark science fact also changed everything. I was in tenth grade Biology, a required class that I had been dreading since first grade, when I first heard I’d be compelled to slice up a live frog some day. I hadn’t heard of menstruation yet so this was the biggest horror I thought I’d ever have to face. But there I was in Biology class and Mr. Kosek was teaching us about stoma pores. Which was one of the coolest things I’d ever heard of.

I vaguely understood that plants “breathe,” but I’d never given any thought to a mechanism. This was normal for me. For instance, not knowing anything about construction, I thought walls were impenetrable, until Amy Cook accidentally sent her butt through one while roughhousing at a slumber party, and there it all was, the whole story, gypsum dust and drywall and a peeved parent. Similarly, I knew plants respired, but I didn’t even think to wonder how.

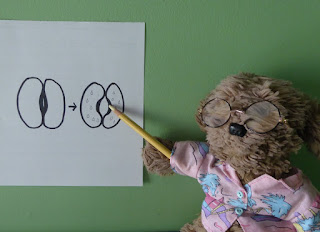

Stomata are awesome. Consider a leaf. It is made up of legions of cells. But some cells are specialized: the paired guard cells of the pores. Stomata are the plant’s means of facilitating gas exchange. That’s right: they are sphincters. Stoma pores close up when water is scarce, and open when there’s plenty. But here’s how: they consist of two fairly large cells shaped like kidney beans, lying side by side in such a fashion that the concave portions meet up and, together, form a hole. Or, if you prefer to see it that way (and many do), they are like a set of matched buttocks, at rest. The portions of the two buttocks that form the hole are thicker and less elastic than the surrounding portions, like a constriction in a balloon, so that when the cells plump up with absorbed water, they bend toward each other and the hole becomes larger. At this point, you may prefer (and many do) to abandon the “buttocks” visualization and go back to the kidney beans. The point is, when there is enough water in the plant, the water can escape through the hole, and when water is scarce, the buttock beans go slack and the hole shuts down, and the plant retains its water. Nothing could be simpler, or more ingenious.

Stomata are awesome. Consider a leaf. It is made up of legions of cells. But some cells are specialized: the paired guard cells of the pores. Stomata are the plant’s means of facilitating gas exchange. That’s right: they are sphincters. Stoma pores close up when water is scarce, and open when there’s plenty. But here’s how: they consist of two fairly large cells shaped like kidney beans, lying side by side in such a fashion that the concave portions meet up and, together, form a hole. Or, if you prefer to see it that way (and many do), they are like a set of matched buttocks, at rest. The portions of the two buttocks that form the hole are thicker and less elastic than the surrounding portions, like a constriction in a balloon, so that when the cells plump up with absorbed water, they bend toward each other and the hole becomes larger. At this point, you may prefer (and many do) to abandon the “buttocks” visualization and go back to the kidney beans. The point is, when there is enough water in the plant, the water can escape through the hole, and when water is scarce, the buttock beans go slack and the hole shuts down, and the plant retains its water. Nothing could be simpler, or more ingenious.

We never sliced up a live frog. There was an earthworm and there was a pickled piglet. There was so, so much more. Science class was the hypodermic syringe of joy, and I was ready for an injection. I even ended up with a degree in Biology. It is a wonder in itself.

Because I thought I would be a writer.

Your other thoughts took that first thought and ran with it. You are most definitely a writer. With a degree in biology, so when you write about this stuff, it is fun and educational to read, rather than a stuffy, boring school text book.

Honestly, I think it was better in a way that I came to writing so late. Otherwise I might have run out of words by now.

Spark bird? Never thought of it that way, but when I did it was the Black-Throated Blue warbler. I think I liked biology because of all the sex. What's not to like? I mean if it wasn't for sex the planet would just be a rock floating through space

…instead we're rocking' the place!

BTB Warbler mine too: he was having dust-bath in lane behind house in downtown Ottawa, early October 2006… My birding madness ensued and lastingly.

A mighty fine wobbler that we don't have here.

I never heard the term "spark bird". I guess in my case (although I don't remember), it was probably my paternal grandfather's budgie. I was besotted with birds from a very early age, and that seems to be my first exposure to a bird close-up. Jerry the budgie must have really made an impression on me, because I've been bird-crazy ever since.

I had a parakeet named Duffie. Duffie did not do it for me, because she was clearly a poor substitute for the dog I really wanted. "City's no place for a dog," my dad said, who grew up with dogs and cats and chickens and a BURRO, but to be fair he was definitely not in a city.

I also parlayed my thwarted dog-love into a fine and huge and (for my parents) indulgent collection of stuffed animals.

Thanks Murr for the science lesson.

Painless enough, huh?

My spark bird was the mocking bird. Then came the cardinal and scissor tail flycatcher. None of these live in this area even though I have issued many an invitation when visiting their preferred habitat. Guess the bug hunting is better there.

We don't have either one and I'd be quite tickled with either. I've never even seen a scissor-tailed flycatcher. Would I absolutely HAVE to go to Texas?

Oklahoma might be a little closer by a mile or 2.

I could settle.

My Biology teacher was Mrs Bell. She had specs much like those worn by Pootie the Sage, but I don't recall her ever wearing a blouse like that. And I think I WOULD'VE remembered!

That is not a BLOUSE. That is a perfectly acceptable and manly Hawaiian shirt.

Spark birds and spark facts make the dark places light again.

Jealous of your rain though. Very jealous.

Well it lasted for about a quarter inch. And hasn't come back. Still, I don't blame you.

What an awesome title!! I couldn't imagine what was coming …

Now you'll never look at a petunia quite the same way again.

"the fragrance Life dabs behind its ears"

Ah, poetry, Ms Murr. As always, thanks.

There's a word for it too. A new word. Petrichor?

Will add petrichor to my vocabulary; however, will remember your poetic words the next time I'm aware of that "after the first rain pleasant smell."

If I were ever to get another tatoo, I think it would be a stomata. Green, of course.

Keeping in mind, of course, that everyone will think it's a butt.

Thanks for petrichor, a lovely word, although I like your description better. My spark birds was a flock of cedar waxwings swooping into a loaded holly tree like a bad boy biker gang, all swept back hair and attitude.

You could do a lot woise than that, that's for sure. Ain't they spiffy?

I think I said this last summer (or maybe earlier this summer), but we have had the wettest July/August in memory, here in DC!! I have repeatedly commented to James that "we might as well be living in goddam Seattle", which (along with Portland) is his idea of a great climate. So we've gotten all of your rain over the past 57 days or so. At least here, the sun will come out in between showers…and BTW, I think you should just go and teach Biology to high-schoolers — you are **so darn good** at explaining stuff!! And kids would simply adore you, too. Just a thought, in case your retirement (and federally-funded pension, that no, I"m not envious of) gets boring. xx

We rarely have a wet summer though! Our wet season is "winter," which lasts from October to the day after the Rose Parade in mid-June. And I think I would have loved teaching. That never once occurred to me until a few years ago. Also, if it helps, my Civil Service pension is a lot skinnier than people assume. The trick is to not need much!

This is a really good idea that you have going on. manufacturing

ซอมบี้