As a writer, I have observed that my output improves dramatically if I pause now and then to play Solitaire. It is so fruitful that I no longer even worry I’m wasting time, and I just go ahead and play whenever the mood hits.

As a writer, I have observed that my output improves dramatically if I pause now and then to play Solitaire. It is so fruitful that I no longer even worry I’m wasting time, and I just go ahead and play whenever the mood hits.

A typical session might go as follows: black queen on red king, black six on red seven, turn, turn, OMG Camilla needs to be kidnapped and Hattie totally loses her shit in the next scene, three on ace.

It’s reliable and cheaper than running a hot shower all day, which is the other way to produce ideas. But I’ve been at a loss to understand how it works.

In order to understand how creativity works, or any thought process at all, you must know a little about neurotransmission. Fortunately, that’s exactly the amount I do know about neurotransmission.

Neurotransmitters are chemicals that poot out of the pointy axon end of a neuron and get gobbled up by the fluffy dendrite end of the next neuron over. It’s the way they communicate. Without neurotransmitters, all our cells would just be a jumbled collection jostling each other on the platform, wondering when the train would arrive. But with neurotransmitters, our cells are lined up and whispering to each other in sequence, such that “Take your hand off the burner” eventually arrives in the spinal cord as “Tag Old Stan in the bunghole.”

The first named neurotransmitter was discovered in 1921 by a guy named Otto, who got to name it. He called it Vagusstoff, but he was wrong, it turned out to be acetylcholine. Anyway, ol’ Otto suspended two beating frog hearts in saline solution and molested one of them, causing it to slow down, and then the other one slowed down too, even though it was not otherwise involved. Also, all the frogs within a ten-mile radius dug deeper down into the mud.

The neurotransmitters in the brain cross over a gap between neurons called a synapse (Greek for “hole in the head”). There are gobs of neurons in the brain, and if you have a very small head like I do, they’re packed in really tight. In addition to the neurons, there are even more cells called glia. They are not well understood but appear to be the support crew. They’re either tightening bolts or sending out for sandwiches. In addition, they keep the neurons from rubbing up against each other and chafing.

It’s not really known if the adult brain continues to create neurons. For a while there it was thought to, because this was observed in rat brains. People were really pumped about that, because they were pretty sure the standard neuron allotment wasn’t cutting the mustard. Recently, it’s come to light that this might be a rodent thing, and primates more or less make do with what they started with. This would be depressing were it not for the fact that we’re already not doing much with the ones we have.

|

| Synaptic pruning in process. |

Furthermore, the adult brain is a sleeker model than the child brain, because during adolescence the brain undergoes something called “synaptic pruning,” in which some 50% of the neuron connections are tidied up and disposed of. Theoretically this makes the adult brain more streamlined and efficient, but it’s possible this is more of a process of civilization for the good of the species as a whole; a process by which humans transition from a life of unbridled masturbation to overeating, TV, and quiet desperation.

Back in oldener times, the brain was thought to be a wired-up electrical model. This was a daunting analysis in the days when people could devote hours to unscrewing every light on the Christmas tree to find the bad bulb. Nowadays we have a more nuanced understanding of brain processes, secure in the notion that if things go wrong we can always unplug, wait a few minutes, and plug back in.

And that’s where the Solitaire comes in.

I tend to think of the brain as a computer, so maybe the synaptic pruning is just the deletion of files or apps that are no longer used (how to kill and cook a mammoth) to free up space for files that are being used (how to text while driving and drinking coffee at the same time.)

I'm down to "How to not fall down" and there's been some pruning there, too.

OMG, I love the way you write!! Here's something of mine:

FISHDUCKY’S THEORY OF MEMORY

Are you familiar with the fishducky theory as to why our memory seems to disappear as we age? If not, don’t worry. I’m going to tell you. What was I talking about? Oh, yes–memory. If you subscribe to the theory, as I do, that the brain is like a computer, then you know that it has a finite number of memory bytes. As we age, gravity pulls these memories down, filling first our feet, then our legs, our bellies & butts (which would also explain why many older people seem to have gained weight in these areas) & finally reach our brains, which eventually become full. Since humans don’t have a DELETE key, there is simply no room for new memories. This is why we people “of a certain age” can remember who sat next to us in the third grade but have no idea of what we ate for lunch yesterday. We are NOT forgetful–WE ARE SIMPLY FULL!!

Maybe, hon–but my delete key is active and quite possibly stuck in the "on" position!

Fishducky, I LOVE this!!!!!

Remarkable how this matches my own experience. My brain is a file cabinet. All the drawers are full. The top one is overflowing. There is detritus all around. The stuff on the ground is forgotten stuff, S

tuff I no longer renumber. And I'm constantly surprised when it happens yet again. Amazing, being 81.

"Remember". Typo.

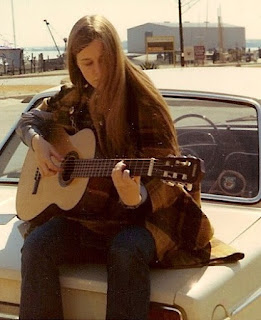

I *adore* this picture of you playing guitar. Very Francoise Hardy /mid-late 60s. Ahhh, youth!

I think I would have paid more attention in biology class if you were my teacher.

It has only been in the last few years that it occurred to me I would have been happy as a teacher, but I have no regrets. About that.

D'uh. You ARE a teacher.

*goes to the corner for sassing the teacher, again*

Fortunately for you, I like my students sassy.

Humans transitioned from a life of unbridled masturbation? When was this. Asking for a friend.

Some have not entirely transitioned.

I deleted a lot of my neurons unintentionally a long time ago which explains a lot about me. Is that you playing 'Blowin' in the Wind'?

That is probably me playing Tom Rush.

Tom Rush was beautiful. His voice sounded like he looked, too. Come to think of it, so did Dylan’s. Also: I once did a lot of parenting therapy. Mom and Dad would invariably get one of those light-bulb-turning-on looks when I explained about the teen brain being in defrag mode. Quite often, that explanation would let them love their kid again.

They bought that, huh?

I find myself wondering whether that teenage pruning is another version of the 'she said it was cold and I should wear a coat. I'll show her…' thing?

Sometimes the pruning just makes everything bushier.

I had the same Volvo, same color. You could fit lots of people in that trunk….if you were sneaking into the drive-in movie…not that other thing.

That was a '68, I think. First square year. My dad's car. The occasion was going to the Outer Banks for a total solar eclipse!

And these days we go to the Banks for a monetary black-out.

Oh dear.

Strangely (for me), I can't think of a comment. Maybe my synapses are messed up and I just need to go play Solitaire.

Sudoko works too. Try it and get back to us.

If the size of my bum is anything to go by, my glia spend far too much time sending out for sandwiches than they do in tightening up loose bolts. I can feel the empty spaces in my brain getting larger as information just drops out.

See, right there, you made a sentence that has never been formed before in the whole world. I love when that happens.

Did you know (of course you do, I'm heading into a rhetorical question) that slightly different arrangements of neurotransmitters and receptors make our entire selves putter along like Dad's 1926 Model T (in my case) or in better built models, new Audi's or even the latest Porsche? Damn, I was hoping I was building more neurons. Certain neurotransmitters in skeletal muscle have a three day turnover rate, so you always have a fresh supply coming along. Sadly there aren't any of those in the brain.

OK, perhaps you can explain why your delightful description of human neurotransmitters makes me think of the hydro-pneumatic suspension system employed by Citroen in lieu of steel springs? Maybe because they are both about systems that transport stimuli with the goal of producing a response? https://youtu.be/g8HzCuJoeaA Or perhaps my filing cabinet is just too full, and this is some of the detritus lying on the floor around it, as someone commented above? 🙂